Pluridens and the insane, incredible, neverending diversity of Moroccan mosasaurs

Why are there so damn many mosasaurs in Morocco?

Pluridens serpentis, a new mosasaur from the late Maastrichtian of Morocco. Art by Andrey Atuchin.

Recently my colleagues and I described a new species from the latest Maastrichtian of Morocco, Pluridens serpentis. Pluridens was a mosasaur- an enormous marine lizard, growing up to perhaps eight or nine meters in length, a bit like a Komodo dragon but with flippers instead of legs, and a shark-like tail. Mosasaurs were the dominant marine predators at the very end of the age of dinosaurs, and the Moroccan mosasaurs were the last mosasaurs on Earth- contemporaries of the last dinosaurs, animals like T. rex and Triceratops. And it’s the third new species to be described from the Maastrichtian of Morocco in less than a year. Just how many species were there?

Probably a lot.

Pluridens, with the related genus Halisaurus for scale, and Homo sapiens. Note the size is somewhat speculative given that we don’t yet have the skeleton, just a skull and jaws. But it got pretty big.

There are 10 reported species from the latest Maastrichtian, the very end of the Cretaceous period, in Morocco. If you include Pachyvaranus, which may represent a dolichosaur- a long-bodied relative of the mosasaurs- that brings you to eleven. Yet we’re probably not even close to finding all of them yet. If I had to guess, I think there were probably between 20 and 30 mosasaur species. How could there be so many species? Well, consider modern marine mammals.

Marine tetrapod diversity

Marine mammals are in some ways the closest thing we have to mosasaurs today, and they show modern marine ecosystems support a lot of species. Hawaii, for example, has 20 marine mammals- 18 whales, and two seals. Hawaii isn’t even all that diverse.

England, not known for whale-watching tours, has a total of 30 whale species and 7 seals. South Africa may have the most diverse marine mammal fauna in the world- 37 species of whale and two pinnipeds, for a total of 39. That’s a lot of species.

And tday, Morocco has 26 cetacean species… so why not 26 mosasaurs?

If you add up everything, you get even more species. Worldwide, there are thought to be 89 species of whales, dolphin, and porpoise, 33 seals and sea lions, four sea sea cows, and one sea otter, for 137 species total.

Remarkably, we keep finding new whales, so we don’t seem to be done yet. We’ve continued to identify several new dolphin species and beaked whales in the 21st century, even two species of baleen whale- Omura’s whale, in 2003, and Rice’s whale, in 2021, in the middle of a pandemic. And not even somewhere obscure like Antarctica, but off the coast of Florida.

Are we scientists just bad at our jobs, that we can overlook something as large as a whale? Well, it’s hard to study animals that spend their whole lives at sea, often offshore, surfacing only to breathe. And animals that look very similar on the outside can be genetically very distinct- the development of DNA sequencing technology has vastly improved our ability to recognize species, so we keep “finding” new species of everything- lizards, frogs, birds, monkeys- and even whales- that have been right there in front of us. These are called “cryptic species”, and it’s been a major thing in biology (and hints that anatomy may lead us to underestimate the number of species out there, which obviously has implications for paleontologists studying bones).

The number of marine mammal species would be higher except for several recent, human-induced extinctions- the Chinese river dolphin, the Japanese sea lion, and the Caribbean monk seal. In short, marine ecosystems can support a large number of large animal species.

Mosasaurs weren’t the only marine reptiles in the Late Cretaceous. There were also plesiosaurs, giant sea turtles, and crocodilians. Still, it’s not inconceivable that there were over a hundred marine reptiles at the time, with mosasaurs probably making up most of that total.

Now, it’s possible there were fewer marine reptiles than marine mammals today. One reason is milk. A baby sperm whale eats the same food as the mother- giant squid and large fish- but indirectly, after she converts this food into milk. So a young whale occupies the same place on the food chain as an adult- it doesn’t compete with smaller porpoises and dolphins for small stuff. But the young of giant mosasaurs had to feed themselves, so they would have competed with smaller species- perhaps reducing the number of small species the ecosystem could support. So maybe there were fewer marine reptiles than marine mammals.

On the other hand, there are reasons to think marine animal diversity could have been even higher than it is today. It was the Cretaceous, when a greenhouse climate prevailed. To the extent that higher temperatures drive higher diversity (a lot), there might have been even more species than today.

Or we could compare apples to apples, or reptiles to reptiles. There are actually a lot of marine reptiles alive today. There are 69 sea snake species, eight sea kraits, three filesnakes, a marine iguana, and seven sea turtles, for a total of 88. But whatever our point of comparison- marine mammals, or marine reptiles- it suggests the oceans can support a high diversity of marine animals.

But if that’s the case, what’s so special about Morocco?

The causes of Moroccan mosasaur diversity

Its important to keep in mind sampling effects. In any ecosystem, there tend to be a few common species, more uncommon species, and many rare species. Consider these sightings from a whale watching company in the Azores. There are 17 species. A few are encountered routinely, others on less than 10% of the trips, and still others on a tiny percent of trips. If you want to find all the species, you have to keep sampling the habitat, repeatedly. You’d need to spend thousands of dollars on whale-watching trips if you wanted to see all 17.

The same is true of paleontology. When digging, we mostly find the common stuff, occasionally find the uncommon things, and we rarely if ever find the really rare stuff. We almost never get a complete picture of the diversity, because we’re rarely able to sample a fauna completely, unless you’re dealing with really common fossils, like clams, or microscopic plankton.

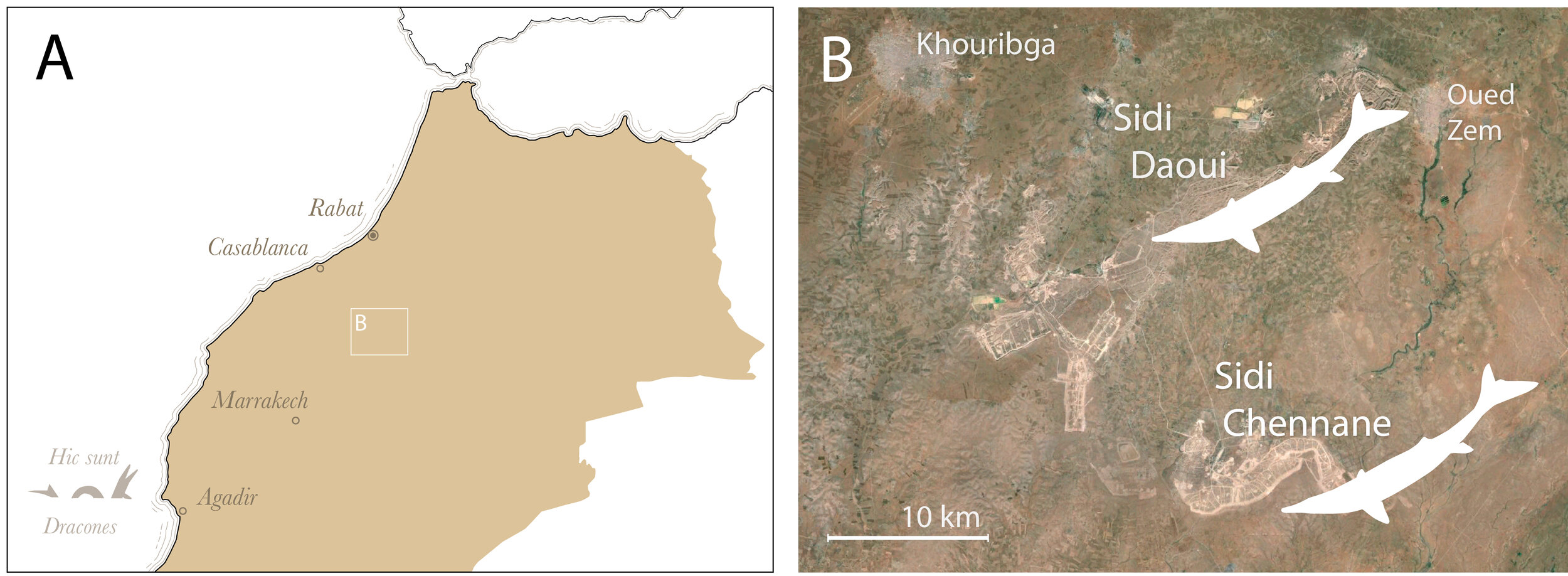

The Khouribga phosphate mines as seen from space (Google Earth). The image is about 50 km (30 miles) East-West. The phosphate mines have created a giant fossil dig- uncovering huge numbers of fossils, and new species.

The phosphate mines of Morocco, however, are different. They are enormous, stretching out over tens of kilometers, and extraordinarily productive- dense bonebeds stretching in all directions. It’s possible they have produced more marine reptiles than any deposit in the world. That means that we get a much fuller picture of diversity from Morocco than other places, like the mosasaur faunas from New Jersey, Alabama, or the Netherlands, which are less well sampled. Quantity has a quality all its own.

The wonderfully preserved skull of Pluridens serpentis from the Moroccan phosphates, one of many beautiful specimens from these beds. It’s the first time we’ve seen a skull for this genus, and tells us a lot about its evolution and biology.

We’re moving past the common things, like the ubiquitous Halisaurus and common Eremiasaurus, and starting to find uncommon, strange things, animals like Pluridens, known from far fewer specimens. And we’re finding even very rare, weird things, like the bizarre Xenodens, which is known from just a single, lonely jawbone out of the hundreds of mosasaur specimens produced by the phosphates. Hell, we’re even finding dinosaurs- in a marine deposit of all places- making Morocco one of the best places in the world to study African dinosaurs from the end of the Age of Dinosaurs.

Xenodens calminechari by Andrey Atuchin

The lone jaw known for Xenodens

So clearly sampling, the simply insane number of mosasaurs coming out of this vast, rich dig, has something to do with the insane diversity. But is it just an issue of having a lot of fossils?

Probably not.

We actually do have very good sampling from the earlier Niobrara Chalk of Kansas, for example- hundreds of specimens, many articulated, dating to around 82-85 million years ago. But mosasaurs just don’t seem to be nearly as diverse here. There are a decent number of species reported, but these rocks span 5 million years, so probably all these species didn’t actually live there at the same time. Tylosaurus nepaolicus seems to be replaced by Tylosaurus proriger, for example- these species may never have met, any more than you’ve met an Australopithecus.

And the Kansas mosasaurs seem to have a far narrower range of tooth shapes and skull shapes. They’re just not doing the same range of things as the Moroccan mosasaurs, which have all these adaptations.

My guess is that the Kansas mosasaurs are less diverse in part just because they’re earlier. Evolution takes time, particular to do something complicated, like turn a little lizard into a giant sea serpent. After an initial radiation of small marine lizards in the Cenomanian, starting around 100 million years ago, the first, primitive mosasaurs appear in the Turonian, about 94 million years ago. And so when we get to the Kansas chalks, 87 to 82 million years ago, mosasaurs just haven’t had a lot of time to evolve new forms and species- to diversify into all the crazy forms we get in Morocco, 66 million years ago. The Kansas fauna is just a far more monotonous fauna- Tylosaurus, Clidastes, Platecarpus, over and over and over again- because evolution hasn’t had time to make things interesting. So part of the answer may just be that Morocco samples a very diverse point in time for mosasaur evolution.

Platecarpus, probably the most common mosasaur in the Niobrara chalk of Kansas. Studying Kansas mosasaurs, you will see Platecarpus over, and over over, and over, and over, and….

But then, the Maastricht of the Netherlands and the Navesink of New Jersey, which also date to around 66 MYA, don’t seem to be as diverse as Morocco, even taking into account the fact that they have fewer fossils. You don’t seem to get the same range of teeth, for example, and teeth are fairly common, so less affected by sampling. Time seems to be part of the answer, but not all of it.

The other thing that may make Morocco so diverse is its location. It’s closer to the equator, and in general, you tend to get more species at lower latitudes. That probably is driving mosasaur diversity up, since that’s a major driver of diversity today.

But on top of being closer to the equator, Morocco seems to be an extremely high productivity environment. The reason these mines are exploited today is because they have vast amounts of phosphate, in beds meters thick, stretching for thousands of square kilometers. The Cretaceous phosphate layers are made from bits of bone from fish, and shark teeth, and coprolites- and mosasaur skeletons- which are then ground up to make fertilizer (this, unfortunately, will probably be the fate of most of the mosasaurs in the mines). Basically, the Cretaceous phosphates of Morocco are a bunch of ancient bone meal. And that is the result of an incredibly high productivity environment, fed by nutrient-rich waters upwelling from the bottom, with millions of sharks, and fish, and marine reptiles dying there over millions of years. And since modern upwelling zones have a high diversity of marine mammals like whales, it’s probably the same for marine reptiles in the Cretaceous.

So not only Morocco’s mosasaurs record a very diverse time in mosasaur evolution, they also represent a very diverse point in space. In other words, we seem to have hit an ancient biodiversity hotspot.

Sidi Daoui and Sidi Chennane are only a few kilometers apart, but Sidi Chennane has many more species.

What’s remarkable is that this diversity is variable even within Morocco, over distances of tens of kilometers. At Sidi Daoui, near the town of Oued Zem, we have a pretty diverse fauna, and tons of mosasaurs- that’s where we get most of the new Pluridens serpentis fossils from. But maybe 15-20 kilometers away, we have the Sidi Chennane mines. And here we get all our Sidi Daoui species like Eremiasaurus, Halisaurus, Carinodens, Mosasaurus beaugei, and Pluridens serpentis- plus others like Globidens, Prognathodon currii, and Xenodens- species which we never, ever get at Daoui. And this seems to be real- we don’t even find the teeth of those species at Sidi Daoui, which produces thousands of teeth!

So with Morocco we have a hotspot. It’s the right place, and the right time to hunt mosasaurs.

But with Sidi Chennane, we have a hotspot within a hotspot.

Why is Sidi Chennane so much more diverse? Hard to say. It’s possible the conditions- water depth, temperature, currents, distance to shore- just supported a much richer fauna a few kilometers away. On the other hand, it’s hard to believe the mosasaurs living at Sidi Chennane never swam past Sidi Daoui , given how large the ranges of modern marine mammals are; even if they did so rarely if so we’d still expect to find the odd tooth of a Globidens there.

That makes me think it’s possible that they’re sampling slightly different points in time, a few tens or hundreds of thousands of years apart. Perhaps there was a change in climate, or currents between the two times, and here we’re sampling that slightly more diverse interval, when species migrated in for whatever reason. We don’t really know.

But it tells us that we need to be careful about making claims about global diversity from small areas. For instance: was the Campanian really an incredibly diverse time for dinosaurs? (Maybe? Or maybe it’s just Dinosaur Park is a hotspot, and the Hell Creek isn’t?)

Whatever the reason- the time, the place, the currents, the vast number of fossils (probably all of these things)- Morocco’s marine reptiles are astonishingly diverse, and the more we sample, the more we’ll find. There’s probably no end to these mosasaurs and other species, at least not for the foreseeable future. And some days I despair that I’ll die before we finish working on all of them. On the other hand, this offers a degree of job security. Having far more species than you know what to do with is, for a paleontologist, not a bad problem to have.

Teeth and lower jaw of Pluridens serpentis.

References

Bardet, N., 2012. Maastrichtian marine reptiles of the Mediterranean Tethys: a palaeobiogeographical approach. Bulletin de la Société géologique de France 183, 573-596.

Bardet, N., Jalil, N.-E., Broin, F.d.L.d., Germain, D., Lambert, O., Amaghzaz, M., 2013. A Giant Chelonioid Turtle from the Late Cretaceous of Morocco with a Suction Feeding Apparatus Unique among Tetrapods. PLoS ONE 8, e63586.

Bardet, N., Houssaye, A., Vincent, P., Pereda-Suberbiola, X., Amaghzaz, M., Jourani, E., Meslouh, S., 2015. Mosasaurids (Squamata) from the Maastrichtian phosphates of Morocco: biodiversity, palaeobiogeography and palaeoecology based on tooth morphoguilds. Gondwana Research 27, 1068-1078.

Bardet, N., Pereda-Suberbiola, X., Iarochène, M., Bouyahyaoui, F., Bouya, B., Amaghzaz, M., 2004. Mosasaurus beaugei Arambourg, 1952 (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the Late Cretaceous phosphates of Morocco. Geobios 37, 315-324.

Bardet, N., Pereda-Suberbiola, X., Iarochène, M., Bouya, B., Amaghzaz, M., 2005. A new species of Halisaurus from the Late Cretaceous phosphates of Morocco, and the phylogenetical relationships of the Halisaurinae (Squamata: Mosasauridae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 143, 447-472.

Bardet, N., Pereda-Suberbiola, X., Jouve, S., Bourdon, E., Vincent, P., Houssaye, A., Rage, J.-C., Jalil, N.-E., Bouya, B., Amaghzaz, M., 2010. Reptilian assemblages from the latest Cretaceous–Palaeogene phosphates of Morocco: from Arambourg to present time. Historical Biology 22, 186-199.

Houssaye, A., Bardet, N., Rage, J.-C., Pereda-Suberbiola, X., Bouya, B., Amaghzaz, M., Amalik, M., 2011. A review of Pachyvaranus crassispondylus Arambourg, 1952, a pachyostotic marine squamate from the latest Cretaceous phosphates of Morocco and Syria. Geological Magazine 148, 237-249.

Lapparent de Broin, F.d., Bardet, N., Amaghzaz, M., Meslouh, S., 2013. A strange new chelonioid turtle from the Latest Cretaceous phosphates of Morocco. Comptes Rendus Palevol 13, 87-95.

LeBlanc, A.R.H., Caldwell, M.W., Bardet, N., 2012. A new mosasaurine from the Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous) phosphates of Morocco and its implications for mosasaurine systematics. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32, 82-104.

Longrich, N.R., 2016. A new species of Pluridens (Mosasauridae: Halisaurinae) from the upper Campanian of Southern Nigeria. Cretaceous Research 64, 36-44.

Longrich, N.R., Bardet, N., Schulp, A.S., Jalil, N.-E., 2021. Xenodens calminechari gen. et sp. nov., a bizarre mosasaurid (Mosasauridae, Squamata) with shark-like cutting teeth from the upper Maastrichtian of Morocco, North Africa. Cretaceous Research, 104764.

Longrich, N.R., Bardet, N., Khaldoune, F., Yazami, O.K., Jalil, N.-E., 2021. Pluridens serpentis, a new mosasaurid (Mosasauridae: Halisaurinae) from the Maastrichtian of Morocco and implications for mosasaur diversity. Cretaceous Research, 104882.

Martin, J.E., Vincent, P., Tacail, T., Khaldoune, F., Jourani, E., Bardet, N., Balter, V., 2017. Calcium isotopic evidence for vulnerable marine ecosystem structure prior to the K/Pg extinction. Current Biology 27, 1641-1644. e1642.

Schulp, A.S., Bardet, N., Bouya, B., 2009. A new species of the durophagous mosasaur Carinodens (Squamata, Mosasauridae) and additional material of Carinodens belgicus from the Maastrichtian phosphates of Morocco. Netherlands Journal of Geosciences 88, 161-167.

Schulte, P., Alegret, L., Arenillas, I., Arz, J.A., Barton, P.J., Bown, P.R., Bralower, T.J., Christeson, G.L., Claeys, P., Cockell, C.S., Collins, G.S., Deutsch, A., Goldin, T.J., Goto, K., Grajales-Nishimura, J.M., Grieve, R.A.F., Gulick, S.P.S., Johnson, K.R., Kiessling, W., Koeberl, C., Kring, D.A., MacLeod, K.G., Matsui, T., Melosh, J., Montanari, A., Morgan, J.V., Neal, C.R., Nicholas, D.J., Norris, R.D., Pierazzo, E., Ravizza, G., Vieyra, R., Reimold, W.U., Robin, E., Salge, T., Speijer, R.P., Sweet, A.R., Urrutia-Fucugauchi, J., Vajda, V., Whalen, M.T., Willumsen, P.S., 2010. The Chicxulub Asteroid Impact and Mass Extinction at the Cretaceous-Paleogene Boundary. Science 327, 1214-1218.

Strong, C.R., Caldwell, M.W., Konishi, T., Palci, A., 2020. A new species of longirostrine plioplatecarpine mosasaur (Squamata: Mosasauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Morocco, with a re-evaluation of the problematic taxon ‘Platecarpus’ ptychodon. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 1-36.

Yans, J., Amaghzaz, M.B., Bouya, B., Cappetta, H., Iacumin, P., Kocsis, L., Mouflih, M., Selloum, O., Sen, S., Storme, J.-Y., 2014. First carbon isotope chemostratigraphy of the Ouled Abdoun phosphate Basin, Morocco; implications for dating and evolution of earliest African placental mammals. Gondwana Research 25, 257-269.