The Discovery of Hesperonychus elizabethae

Hesperonychus elizabethae

The discovery of Hesperonychus was a long and tangled quest. One day, I was sorting through some microvertebrates from the Lance Formation, really old stuff, collected by Marsh during the Yale expeditions to Wyoming back in the late 1800s. I pulled out this little toe bone- it was virtually identical to a bone from the second toe- the one that bears the killer claw- of the large dromaeosaur Deinonychus, which was actually a few cases away in the same collections. But this one was from a small animal, about the size of a cat.

It got me thinking.

What puzzled me was the absence of small dinosaurs in western North America. We had tiny dinosaurs like Microraptor from China, and small dinosaurs in the Gobi. Why would we only find them in Asia, and not North America? Could there be small theropods in North America as well?

Going through the Tyrrell collections, I started seeing more tiny dromaeosaur elements. They were typically either classified as juveniles of Saurornitholestes, a wolf-sized dromaeosaur, or else misidentified entirely, and in the bird collections. Their small size was automatically assumed to be evidence that they were juveniles – or birds.

I’d learned from the Tyrrell guys that you could tell juvenile bone. It had a different texture. Juvenile bone was fibrous, like wood. Lots of elongate grooves and pores, a grain to it. Whereas adult bone was smooth, like porcelain.

And this stuff didn’t look like juvenile bone. It looked like adult bone.

At this point, I was pretty sure I had some kind of new, small-bodied dromaeosaur. I did the drawing above at about this time. Obviously a bit speculative- all I had was toe bones.

I also knew I couldn’t prove it. Other scientists would never buy, on the basis of bone texture along, that we had a new dinosaur. I needed something better. I spent years looking. When I visited collections anywhere, I’d keep an eye open, trying to find more of this new animal. I found more claws, more toe bones, bits and bobs, but never anything definitive. Not enough to tail it. This went on for years. Eventually, I gave up hope of ever finding anything that would prove this thing existed.

And then one day I was in the University of Alberta collections. I went through every drawer in every case, and now there was just one case left. The one in the very back. And I went through it drawer by drawer, and now there was just one drawer left. The one at the very top. And, being short, I couldn’t reach this drawer from the ladder.

At this point, I’d long since given up hope of ever actually finding definitive proof that this animal existed. But it was just sheer force of habit; I wanted to look at every bone in the collections.

What I did next was to climb up. I stuck one foot on top of one case, and another on top of another case on the opposite side of the aisle, and pushed myself up to see what was in the top drawer of the upper case. I went through every fossil in that drawer. Nothing.

But there was still ONE fossil I couldn’t see. One fossil, lurking in the very back.

So I reached in, and pulled it out…

And went, WTF is that?

It really didn’t look like much. The element was sort of split, fused at the bottom, with two arms going up. It reminded me of a chevron- the V-shaped bone you see under the tail of a hadrosaur (all reptiles have chevrons, but it was about the right size). But that didn’t seem right. Then I remembered seeing something similar elsewhere.

Then I remembered where’d I’d seen something like this.

Sinornithosaurus, from the Early Cretaceous of China. Note the J-shaped bone in the lower center of the photo- that’s the pubic bone.

Sinornithosaurus, from the Early Cretaceous of China. Note the J-shaped bone in the lower center of the photo- that’s the pubic bone.

It looked like the pubic bone of the dromaeosaur Sinornithosaurus, a microraptorine. So, we had a microraptorine pubis?

Huh.

I was, at this point, underwhelmed. It was a pretty grotty looking bone. It didn’t really seem like it would settle things and anyway, I wasn’t even sure it was a microraptorine. But I decided to get Clive Coy to prep it.

This is how it came back.

A complete, three-dimensional pelvis. It showed a number of clearly microraptorine features- the hockey-stick shape of the pubis, the little processes on the sides. But it also had weird features. The processes were huge and winglike. There were these big divots in the pubic peduncles. The whole thing was fused.

The fusion was cool- the pubes were fused to the ilia. This showed the animal was probably adult. So we could be pretty sure now we had an adult microraptorine, not a juvenile Saurornitholestes.

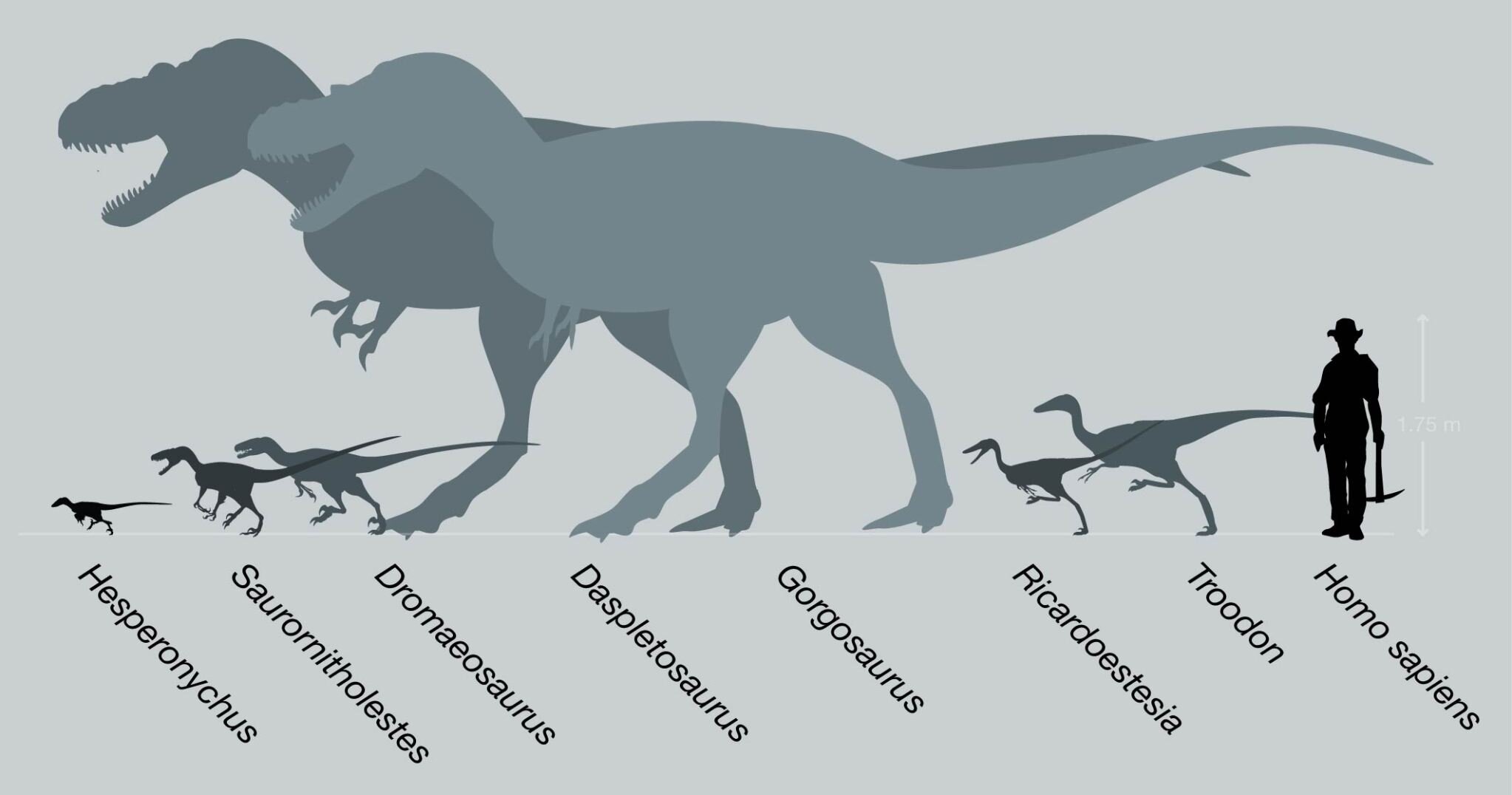

So we now had a full-grown dromaeosaur that was maybe a meter long and weighed about 2 kg- about the size of a small cat.

We named the animal Hesperonychus elizabethae. Hesperonychus translates to “Western Claw”. The species, elizabethae refers to Betsy Nicholls, who 25 years earlier, hired to collect fossils from Dinosaur Park, found the specimen, and later became a Tyrrell Museum paleontologist. I just thought the name sounded better than “nichollsi” which was already used, anyway.

There were small dinosaurs. But not that small. Hesperonychus was small by dinosaurian standards but large by mammalian standards. Most of the mammals at the time weighed less than 100 grams, and Hesperonychus was bigger than even the largest contemporary mammals, animals like Meniscoessus and Eodelphis, which were maybe 500 grams or so.

What’s striking is that even the smallest dinosaurs were big by mammal standards.

So at the end of the Cretaceous, we saw a scenario where mammals were small, unable to compete with dinosaurs for large bodied niches.

Dinosaurs, however, were all large- even animals like Hesperonychus– by mammal standards. They couldn’t compete with mammals for these small-bodied niches.

The situation was stable- and arguably the dinosaurs had the better deal- they probably comprised more total biomass- but it would turn out to be a disastrous strategy for the dinosaurs when the asteroid hit, and everything larger than a few kilograms were wiped out.

Last… this was my first big paper. For me, the revelation came when I sat down and realized I had dozens of projects going on, but no priorities. I asked myself, “what is the most important thing I could have done in six months?” I realized that this paper was that. So I dropped everything, came in from the field, started working. I traveled to NYC and Beijing to get the data for a phylogenetic analysis. I got the paper drafted.

Two days before the deadline for my postdoc application, I hassled the editor. It was a bit high risk, but… could they make a decision? Accepted. At PNAS. I hastily moved it from “in review” to “in press” in my CV, and sent the updated CV off. A couple months later I got a postdoc at Yale. I’ll never know if that made the difference, but this project was where I learned to put your money on your best horses.

References

Paper is here: Longrich, N. R., and P. J. Currie. 2009a. A microraptorine (Dinosauria-Dromaeosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of North America. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106:5002-5008.