The Engimatic Labocania

Why has the carnivorous dinosaur Labocania anomala been so hard to pin down?

A vast plain reaching onward to the farthest serried rimlands blue with haze and the adamantine ranges rising out of nothing like the backs of seabeasts in a Devonian dawn

— Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

MEXICO is full of vast deserts and mountains, sedimentary outcrops uplifted and worn down to expose ancient strata and the bones of creatures from times long past. It’s beautiful from a purely aesthetic standpoint, and as a scientist, wondering what lies in those hills waiting to be found. In many ways, Mexico is a paleontologist’s dream.

Historically, Mexico has seen less fieldwork than the United States. Partly that’s because there’s been less funding, partly because it can be challenging to work there. So relatively little is known of Mexico’s dinosaurs— not because Mexico didn’t have them, or because they weren’t diverse, but just because we haven’t explored enough.

Labocania anomala tooth

The mysterious Labocania anomala

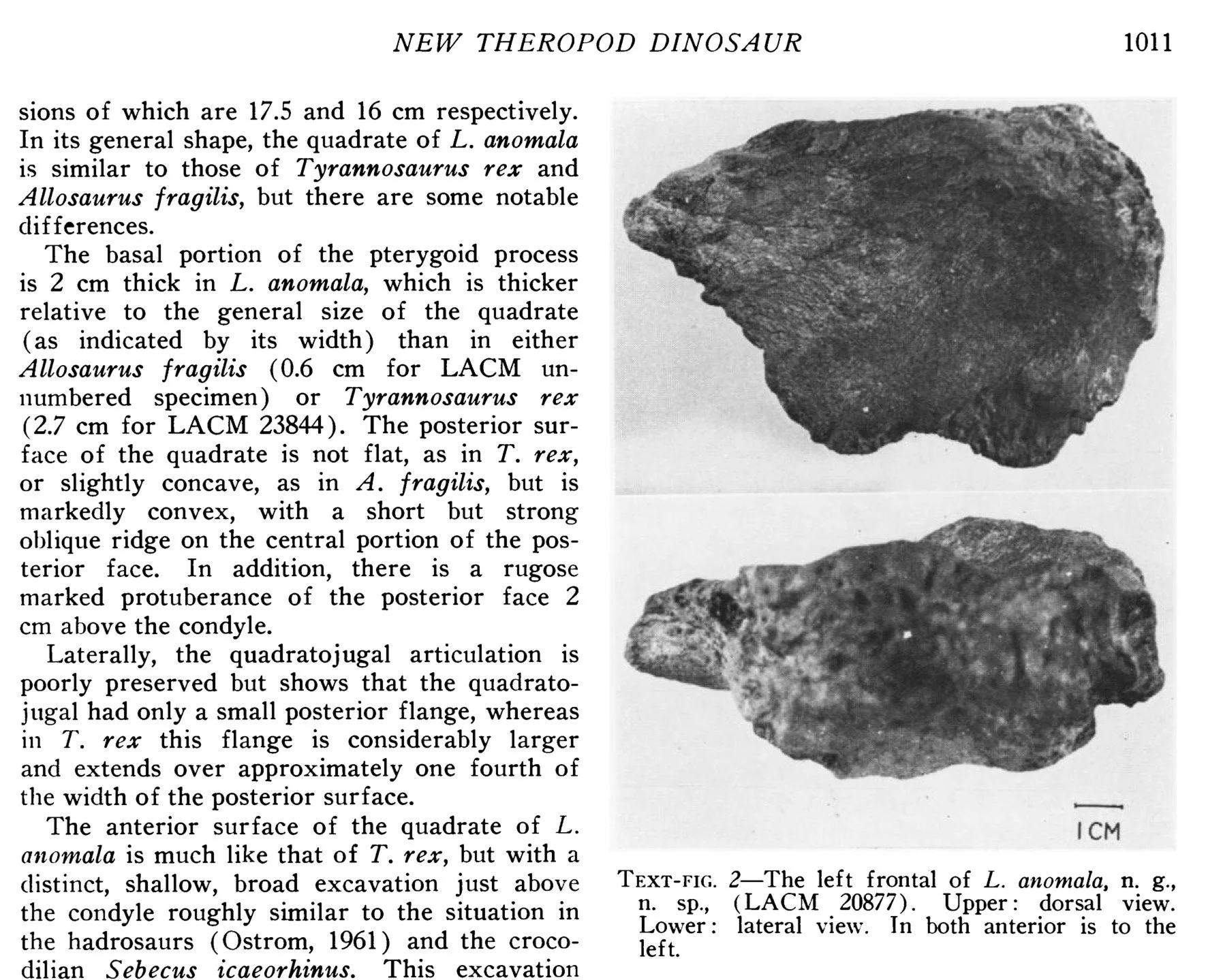

The carnivorous dinosaurs of Mexico are particularly poorly known. One of the few theropods known from Mexico is Labocania anomala. Labocania was reportedly recovered from then Late Cretaceous of the La Bocana Roja Formation of Baja California. It’s fragmentary— all that’s known are a frontal, a quadrate, two maxilla fragments, a few teeth, bits of ischia, and a few other bones. In his original description, Molnar noted what he considered odd features of the animal— it had very thick frontals, and he couldn’t identify a supratemporal fossa.

He compared it to various species— tyrannosaur, abelisaur, carcharodontosaur- without coming to a conclusion. Some years ago I saw the material in Mexico City at UNAM. It struck me as very obviously tyrannosaurid: the ischium has the large, semicircular muscle attachment scar that’s typical of tyrannosaurids, and after all, we don’t have any other big theropods known from North America after the Cenomanian. I left it at that, however. Since, Labocania has tended to be considered as “incertae sedis” and is largely ignored in discussions of tyrannosaur systematics.

Molnar’s 1974 description of Labocania

What’s in the Box?

Recently, I was going through the collections of the Museo del Desierto in Saltillo and came across an undescribed tyrannosaur skeleton from the latest Campanian of the Cerro del Pueblo Formation of Coahuila. It was, shall we say, not the most spectacularly complete dinosaur in the world.

The Cerro del Pueblo tyrannosaur in the Museo del Desierto collections, Saltillo, Coahuila

The tyrannosaur looked like nothing more than tray after tray of boxes filled with irregular, dark rocks. It consisted of maybe a hundred bone fragments in varying states of completeness, eroded and covered in dark desert varnish, a layer of minerals that forms on things left in the desert. The specimen might once have been quite complete. But given by the amount of desert varnish on it, it had probably been out there a long time- thousands of years. The tyrannosaur was probably there before the Apache, before the Indians who came before them. Maybe since the time of the Clovis people, at the end of the last Ice Age. It had been surface-collected twenty years earlier and sitting in a drawer ever since, challenging anyone to make sense of it. So it was a difficult specimen, but I’m sort of addicted to difficult specimens.

Humerus and femur of the Cerro del Pueblo tyrannosaur, from Coahuila, Mexico

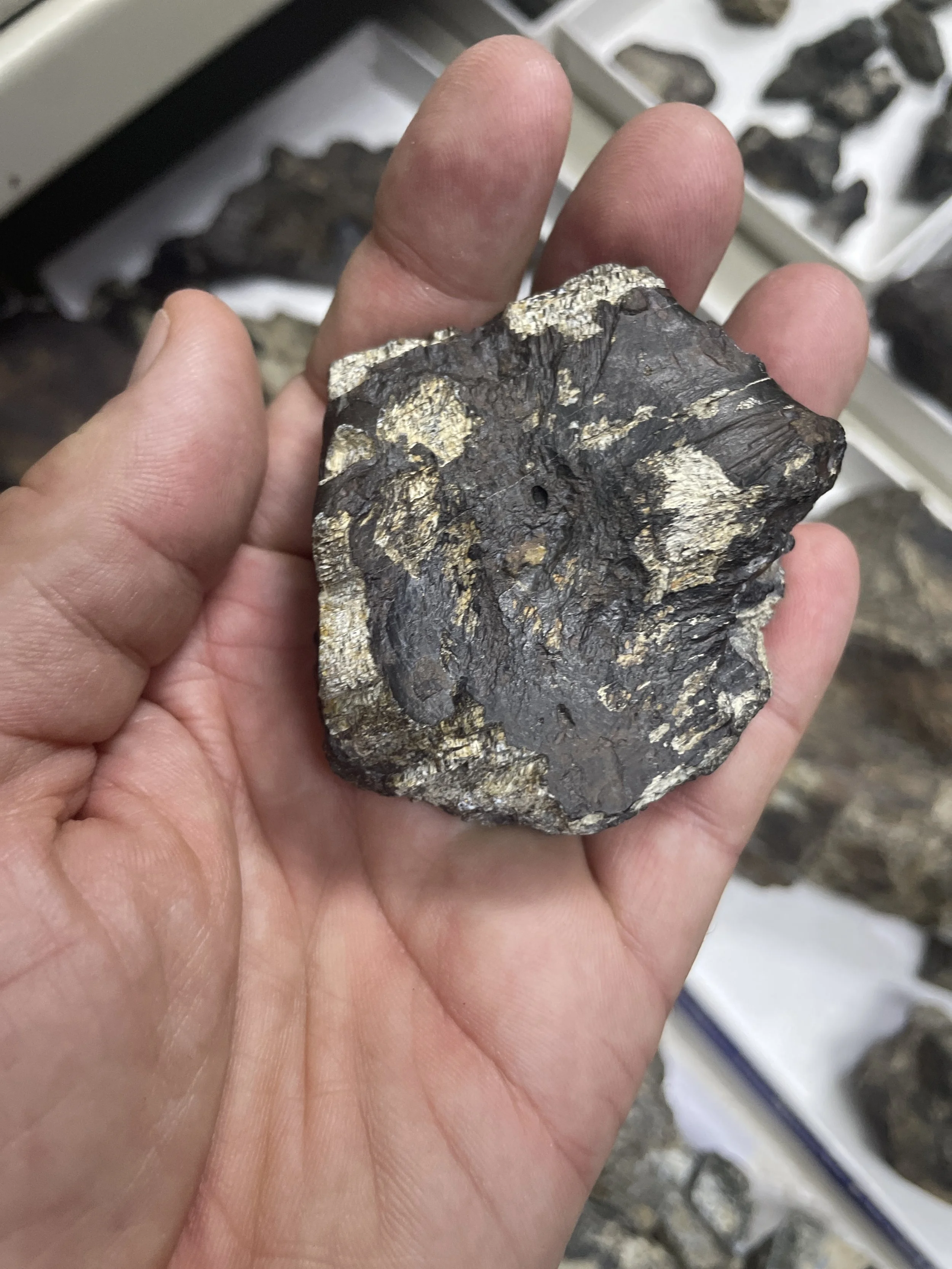

It certainly didn’t look promising, though. With a bit of work, you could reassemble most of a femur and a humerus. There was also part of a metatarsal, and a tibia. There was a piece of bone mislabeled as the frontal which did have a skully look, but which definitely wasn’t a frontal (yes, ‘skully’ is a real word, more or less. It’s an adjective that paleontologists use to describe complex but hard-to-identify bone fragments that look like they might come from the skull, or might not). I’m still not sure what it is (maybe part of the sacral neural arches)? There was a fragment of a lacrimal. A chunk of nasal. And, critically, mixed in with the rubble was a small, quadrangular chunk of bone that represented the actual frontal, and another which was its broken counterpart.

Cerro del Pueblo tyrannosaur frontal

Having recently been involved in Tyrannosaurus mcraeensis, I had a good working knowledge of tyrannosaur skulls. Frontals are pretty diagnostic. And while the specimen wasn’t pretty, neither were animals like Timurlengia (assembled out of isolated bits from a bonebed), Thanatotheristes, Dynamoterror, or Nanuqsaurus. Discussing things with my collaborator Hector, it seemed we could try to make something of this animal.

Some people prefer to work with more complete specimens— to be fair, so do I— but beautiful trophy skulls are vanishingly rare, whereas fragmentary specimens are common. In fact, if you ignore the fragmentary stuff, you’re ignoring more than 90% of the fossil record. Obviously these complete specimens are important— they give us a good picture of what these animals look like, which lets us interpret the fragments. Also, I kinda like puzzles. These incomplete specimens are paleontology on hard mode.

Thinking Zebras

One of the first things we did was cast around for tyrannosaurs to compare the Cerro del Pueblo tyrannosaur to. One of the first tyrannosaurs I looked at was Bistahieversor sealeyi. This is a logical place to start— Bistahieversor is from the late Campanian of New Mexico, maybe a million years before the Cerro del Pueblo tyrannosaur, and just to the north. Dinosaurs show lots of endemism- dinosaurs from Mexico tend to be related to dinosaurs from Texas and New Mexico, not dinosaurs from Canada.

Where you are matters— as the saying goes, “when you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” That’s obviously not a saying of the Maasai tribe from Kenya, or it would go “when you think hoofbeats, think zebras, not horses”. Context is critical, not just the anatomy. And since we were in the South, we shouldn’t think in terms of northern animals like Albertosaurus and Daspletosaurus, but southern things. This saved us a lot of time in trying to make sense of our tyrannosaur.

Cerro del Pueblo Formation tyrannosaur lacrimal (above) showing a very circular orbit

Strikingly, the lacrimal of our Mexican tyrannosaur was almost identical to Bistahieversor. It was strongly curved, implying a huge orbit like in Bistahieversor. It also had a sort of nubbin or process on the lower part of the orbit, like our tyranosaur - which other tyrannosaurs lacked. It seemed we had something like Bistahieversor- although subtle differences in the antorbital fossa of the jugal and the little process suggested a distinct species, as did the time difference (dinosaurs evolve very quickly, rarely lasting more than a million years- so if you have two bones separated by a million years or more, they’re usually separate species). So this hunch- that a Mexican tyrannosaur would be related to other southern tyrannosaurs- paid off.

Which got me thinking. We have a Mexican tyrannosaur. And there’s only one other Mexican tyrannosaur known.

Labocania anomala.

The not-so-anomalous Labocania anomala.

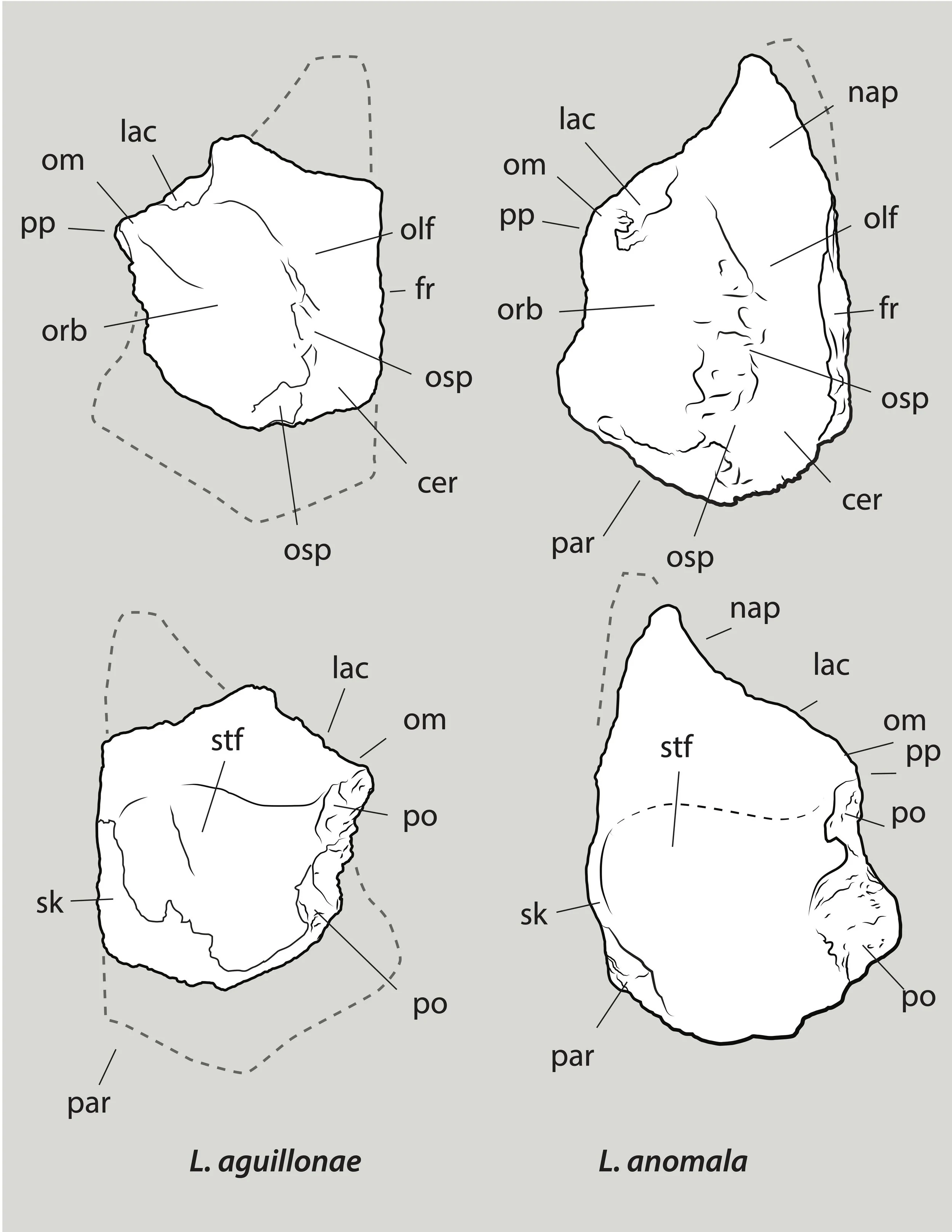

Labocania isn’t well-illustrated (and I hadn’t photographed it when I saw it before) but Hector found some old photos of Molnar’s. The animal was similar to ours in the frontal-lacrimal contact, which tends to run transversely in other tyrannosaurs, but in ours and Labocania makes an angle. Could we have Labocania, or something like it?

Unfortunately, Labocania turned out to be surprisingly hard to find. The first time I stopped by the museum in Mexico nobody seemed to know where it was, and so it was only on a later trip where I managed to sit down with the specimen and take a good look at it. The frontals were strikingly similar to the Cerro Del Pueblo tyrannosaur. Another odd feature is that the teeth had huge grooves running up the sides, like tyrannosaur teeth from the Cerro del Pueblo Formation; T. rex doesn’t have this and neither do tyrannosaurs from Dinosaur Park in Alberta.

A few other things were also made clear. First, Labocania anomala isn’t really that anomalous. Are the frontals thick? Yes. But they’re thick in other tyrannosaurs, e.g. Thanatotheristes and T. rex.. It’s actually pretty standard for a big tyrannosaurine. Another supposed oddity of Labocania is the absence of supratemporal fossae. The frontal’s dorsal surface is eroded, however. So the subtle scars marking the edges of the supratemporal fossa are gone. It’s there, it’s just hard to see. The ischia are (as I’d noticed years ago) classic tyrannosaur, definitely not abelisaurid or carcharodontosaurid. The odd lateral shelf on the “dentary” isn’t unusual: it’s the rim of the antorbital fenestra; the bone is a maxilla.

Why hadn’t anyone figured this out? Well, the fossil isn’t that mysterious. It’s just that nobody has bothered to look closely at the original material very closely since the original, preliminary description, which consisted mostly of line drawings. People were too reliant on the literature. The idea that there was something unusual about this animal ended up being repeated over and over, uncritically, without anyone taking the time to go back and look closely at the original fossils.

To be fair I’m not 100% certain that what we have from the Cerro Del Pueblo is actually Labocania. In fact, it would not surprise me if further study revealed the Coahuila tyrannosaur to be something distinct from Labocania. But the Cerro Del Pueblo tyrannosaur was hard to separate from it, so for the time being it seemed more conservative to put our thing in Labocania. We named it Labocania aguillonae, after the discoverer, Martha Aguillon.

The Southern Connection

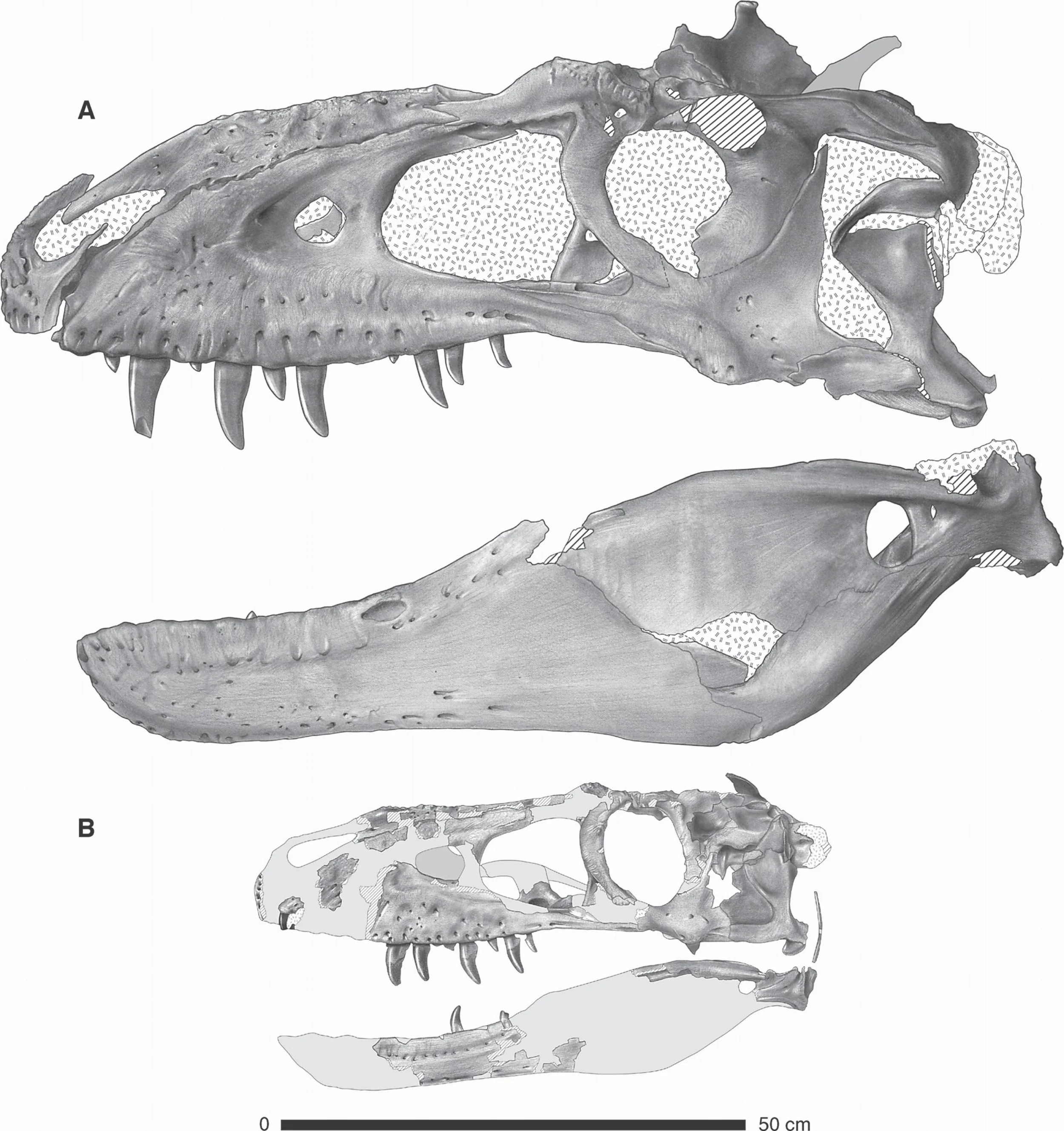

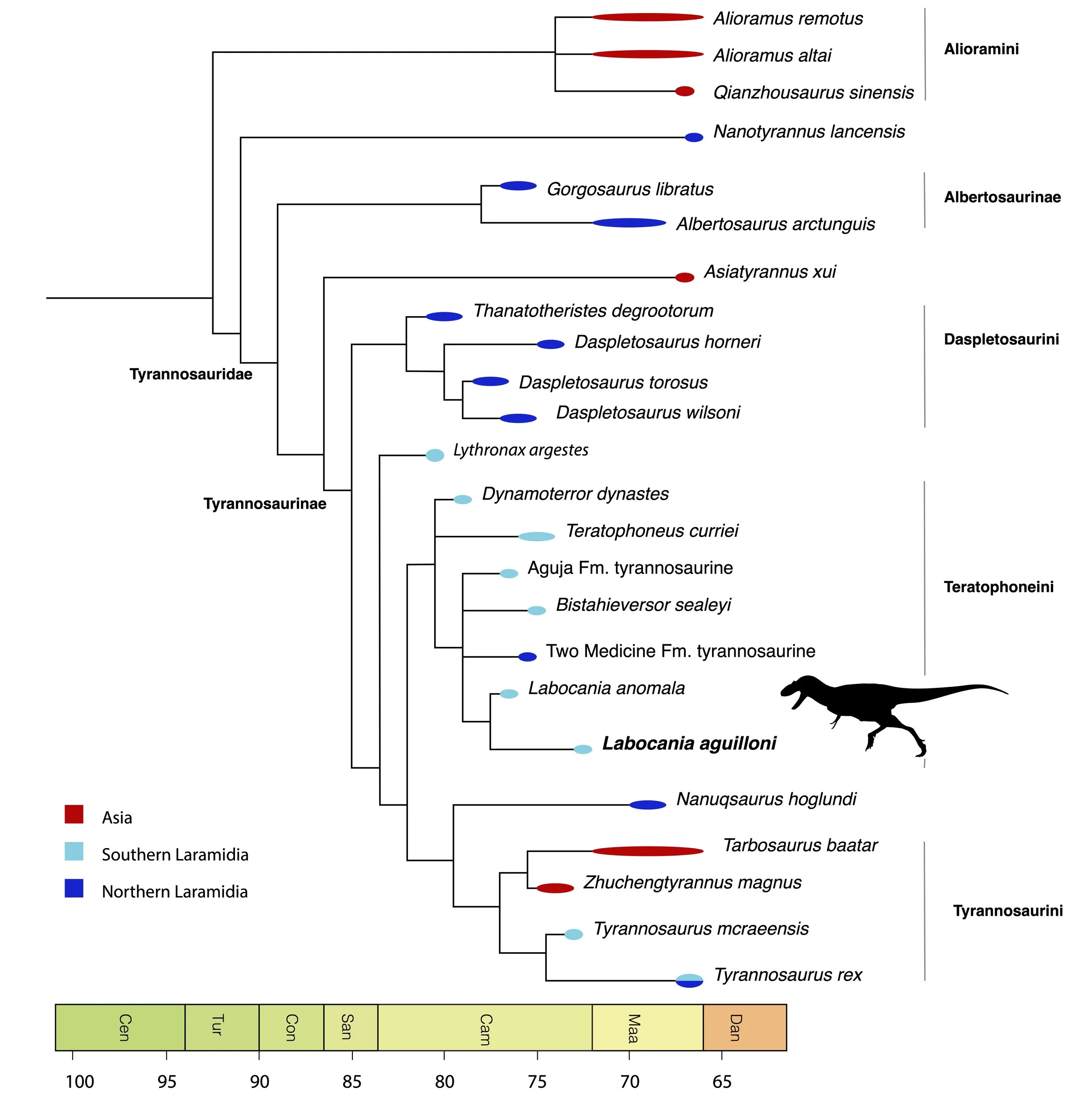

So we had a trio of southern things— the Cerro del Pueblo tyrannosaur, Labocania, and Bistahieversor. So where did these animals go?

A recent paper describing Dynamoterror included a number of southern species— including Teratophoneus, Lythronax and Dynamoterror in a southern clade that was named Teratophonei. We noted a number of similarities that seemed to link the Mexican / New Mexican tyrannosaurs to Teratophoneus. These included a big, circular orbit, and peculiarities of the pelvis, including a rectangular pubic peduncle and a curved ischium. We hypothesize that most of the southern things can be included in Teratophonei (Lythronax, however, has a distinct pelvis and frontal, and may be something else, although what, not I’m sure).

Phylogenetic analysis showing the Southern Clade (Teratophoneini) with Labocaniaanomala and L. aguillonae. From Rivera-Sylva and Longrich (2024)

This southern clade never seems to get as far north as Alberta, although a frontal from the Two Medicine Formation of Montana may represent a northern dispersal of the group. An odd frontal from the Aguja may represent another teratophonein.

This group actually seems to be fairly diverse and widespread- in fact, they seem to be the most diverse group of tyrannosaurs. They are also oddly built— they had large eyes, and fairly lanky limbs, suggesting they occupied a niche somewhat different than that occupied by other tyrannosaurines.

This isn’t the final word on tyrannosaur classification. Doubtless, new fossils and new studies will force us to revise the tree. It would be great to have more of Lythronax, or postcrania for Bistahieversor— there seem to be lots of diagnostic characters in the hips that help tie together Labocania and Teratophoneus, for example. Nanuqsaurus is frustratingly incomplete. But it’s hopefully a step in the right direction. I suspect future finds will show we are broadly correct, and if not, well, that’s how science advances— by rejecting hypotheses.

The Lesson of Labocania

So what to take away from this?

Labocania aguillonae by Andrey Atuchin

The big anomaly around Labocania isn’t so much what it is— the anatomy is very straightforward, the frontal is unambiguously, indisputably tyrannosaurid in all features, and so are those ischia. The teeth are pretty typical of tyrannosaurs. The dentary isn’t odd once you see it’s a maxilla. It’s just that few people ever seem to have taken the time to actually take a look at it closely since the original description. Instead, misinterpretations in the original paper were uncritically repeated for decades.

I appreciate traveling to Mexico City isn’t convenient. But nobody’s forcing anyone to weigh in on this issue with incomplete data, either. Labocania wasn’t a mystery because the fossil was incomplete. It was a mystery because nobody went back and looked. What this means is that if a specimen is enigmatic, go look at the specimen.

References

Molnar, R.E., 1974. A distinctive theropod dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Baja California (Mexico). Journal of Paleontology, 1009-1017.

Rivera-Sylva, H.E., Longrich, N.R., 2024. A New Tyrant Dinosaur from the Late Campanian of Mexico Reveals a Tribe of Southern Tyrannosaurs. Fossil Studies 2, 245-272.