The Dawn of War

I recently finished a first draft of my book, The Dawn of War, which follows the evolution of warfare from apes, to neanderthals, to humans and finally drones and AI. It’s now on to editing.

cover mockup (subtitle yet to be determined….)

Writing this book has been an adventure. It’s taken me from the Tanzanian bush with Hadzabe hunter-gatherers, to the ruins of Rome and the Acropolis.

I visited the ancient walled city of Jericho in Palestine and the modern walled nation of Israel. In Jerusalem I prayed at the place where Jesus Christ was crucified by the Romans, and, if you believe, was raised again.

I saw the Ukrainian steppe where 5000 years ago the Yamnaya set out to conquer the world and dodged Russian artillery in Kharkiv and Shaheds and hypersonic missiles in downtown Kiev and went down into a Soviet nuclear missile silo buried deep under the Ukrainian steppe.

I visited the highlands of Papua New Guinea. which less than 100 years ago still existed in the stone age, and saw how spears and bows were used.

I didn’t know all these things were leading to the book at the time, but here we are.

This is meant to be a big, ambitious, and idea-heavy book and so the big problem is that it’s too long. It’s going to be an interesting process editing it down. A few of the things I learned, in no particular order:

Sweet potatoes were weapons of mass destruction.

Papua New Guinea sweet potatoes

800 years ago, the Polynesians made landfall in South America and met the locals. They exchanged gifts. In this way the South Americans got the chicken, the Polynesians got the sweet potato. Over the next 500 years the sweet potato would make its way across the Pacific and finally arrived in New Guinea. When it arrived in the highlands, the sweet potato revolutionized farming. It grows in poor soils, and cold climates, and its a supercrop- it produces huge numbers of calories per acre. The effect was a wave of destruction and violence that is recorded in Papua New Guinean oral histories six generations later. More food means more kids. More kids means more demand for land. There may have been similar dynamics when corn was introduced into Africa, and potatoes into northern Europe: they fueled population growth and conflict, potatoes fed Napoleon’s war machine and the rise of Russia as a major power.

The obvious implication is that the invention of farming 11,000 years ago probably saw a radical increase in violence. The world has become less violent over time, but this was probably not a linear process.

Warfare Made Cities

The walls of Jericho, West Bank, Palestinian Territories

The first thing people started building when they settled down was walls. At the very lowest levels of Jericho, before they built palaces, or temples, or statues, or even made pottery, they had walls. A primary purpose of building early settlements was probably defense; Jericho was a walled compound.

Further north in Anatolia, in Turkey, Catalhoyuk is built of a series of rectangular mud-brick houses packed edge to edge. There are no windows, no doors, no streets. The only way in was to scale a ladder to the roof, then climb through the smoke-hole to the houses. This was not a bucolic farming village but a fortress. War was one of the earliest and most important drivers of urbanization.

The Spear Made Us Human

The major innovation that made us more than just bipedal apes was the invention of ranged weaponry around 2 million years ago— specifically throwing spears. Throwing spears let us become big-game hunters, and move up the food chain. As we moved up the food chain, we had fewer predators to control our numbers. This led to increased competition for hunting and foraging territories, and something like warfare likely appeared at this time. The remarkable effectiveness of the spear is testified to by the fact that it was a major weapon if not the primary weapon of many civilized armies— Greek and Macedonian phalanxes used spears, Roman legions hurled javelins, medieval knights fought with lances— and even into the 20th century was used in the form of the rifle-mounted bayonet.

The other great human weapon— the club— seems to appear about this time, with healed cranial trauma in Homo erectus, later Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, evidence of war with clubs.

The use of spears for hunting and fighting also led to one of the most peculiar features of the human species— our sex-based division of labor. Men hunted and women foraged for plants; acting almost like two different species. And men waged war. The physical and psychological differences between the sexes took shape at this point. The spear drove the evolution of Man, and also of Woman.

Evolution of human social structures was primarily driven by war

Humans are unusual among apes in our sophisticated social structures. Hunter-gatherers lived in bands, groups of families, which were joined by language, culture and intermarriage into a tribe. The purpose of the large size of this social group is to be able to compete with other social groups to hold, or take, territory. Our unusual sociability is fundamentally an adaption for conflict.

With the appearance of agriculture and herding, the ability to produce large amounts of food in a small area allowed human social structures to become much larger, and more complex. However, the pressure to become larger and more complex was military: large, complex tribes, chiefdoms, and city-states could better defend themselves, and seize land. Over time, nations have become larger and more complex and formed international alliances to deter or wage war.

The Neolithic Revolution Spread By Sea

Spread of farmers out of the Fertile Crescent and into Europe

The Neolithic Revolution saw farming appear along the coast sof Europe first in Greek, then Italy, France and Spain. Even earlier, farming appears on Crete and Cyprus. Farmers were able to use wooden canoes to colonize areas, then slowly drive out or kill off the local hunter-gatherers.

The geography of the Mediterranean was critical to the early, wide spread of farming in Europe. The Mediterrean is largely enclosed by land so it has no strong currents and relatively small waves; it has no hurricanes. It was the perfect place to develop seafaring. It had lots of harbors, and navigable rivers.

The Mediterranean therefore gave Western Civilization a headstart— and later in Greek and Roman times, and in the Renaissance, allowed the spread of ideas, technology and empires. As much as anything this geography may explain why Western Civilization took the lead.

We Speak the Language of Conquest

Almost half the people in the world speak a member of the Proto-Indo-European language family: English, French, German, Russian, Danish, Spanish, Portuguese, Greek, Pashto, Farsi, Hindi.

The similarities in the vocabulary, grammar and sounds of these languages reflect the fact that they descend from a common ancestor tongue, Proto-Indo-European, spoken 5000 years ago on the Russo-Ukrainian steppe. The people who spoke this language, the Yamnaya, were the first steppe conquerors. They scouted with horses, drove their tribes along using the recently invented wheel, and had their agricultural base follow along on hooves— driving cattle, goats and sheep they set up their communities and feed their armies anywhere there was grass.

We speak the languages of these conquerors— and their social structures of this warlike culture were also deeply ingrained in the Greek and Roman societies that form the basis of Western Civilization, which may have made Western civilization more aggressive and expansionist.

War Likely Goes Back to the common ancestor of chimps and humans

Chimpanzee males cooperate to kill chimps from other bands. Although the lack of this behavior in bonobos raises some ambiguity about whether this behavior is ancestral, the fossil evidence suggests chimpanzees better represent the ancestral condition. Chimps, not bonobos, are the key to understanding our ancestors.

We Have Entered an Era of Indirect War

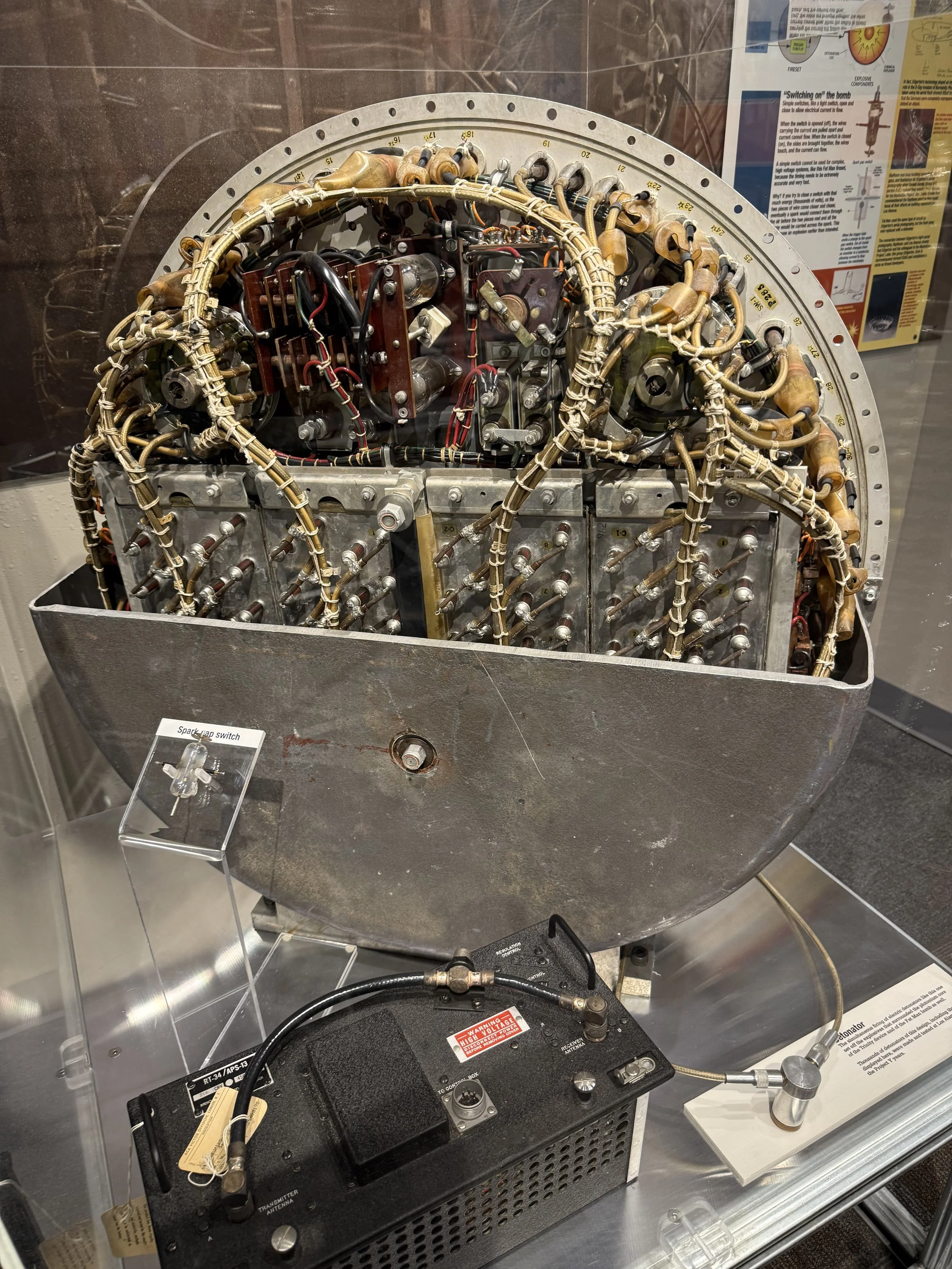

Fireset (trigger mechanism) for a Fat Man style plutonium bomb, Los Alamos Labs, New Mexico

The world has become less dangerous. Although we have become tremendously effective at killing, it has become extremely dangerous. The tremendous destructive power of modern weapons— not just nuclear warheads but cruise missiles, bombers, aircraft carriers, artillery— has made open warfare between major powers risky. This has only slightly reduced the total number of wars but more importantly reduced their scale. The world is less violent than at any point in human history.

While this deters open conflict between powers like the United States, Russia and China, it means we have entered an era of War by Other Means. This includes proxy wars, sabotage, psyops, cyberwarfare and information warfare. This kind of war— Grey Zone Warfare, Hybrid War— is the war we find ourselves in now. One of the dangers of this sort of war, I worry, is that it may sometimes be so subtle that we may not even realize we are at war at all.

Anyway, there’s more— a lot more. There’s so much to include it’s hard to know what to leave out. Hopefully that means that anything that stays in the book will be there because it’s really exciting.