A Dome-Headed Troodontid From the Late Cretaceous of Coahuila, Mexico

A bizarre dome-headed species of the family Troodontidae hints at the high diversity and unique species of dinosaurs in northern Mexico- and at the increasing role of sexual selection in dinosaurs over the course of their evolution.

The Dinosaurs of Coahuila

The deserts of northern Mexico are one of the last frontiers for dinosaur paleontology.

Most of North America has been intensively worked for over a century. Canada, Montana, Wyoming and the Dakotas, Utah and New Mexico have seen extensive fieldwork starting in the late 1800s and early 1900s, starting with the Bone Wars of the late 19th century. There are of course dinosaurs out there still waiting to be found, but fieldwork in the Hell Creek Formation Montana tends to produce the same things over and over— Tyrannosaurus, Triceratops, Edmontosaurus. That’s not to say there’s nothing new there, but most of the common things have been found and we’re now finding the rare species, and so new dinosaurs have tended to emerge slowly in recent years.

Northern Mexico has never really been explored in the same way, though. Field work began relatively late there, in the 1990s. And northern Mexico has never really seen the same intensive exploration as the northern Great Plains. There are reasons for this— the Chihuahuan desert of Northern Mexico is a harsh country, high temperatures make summer fieldwork difficult, huge areas don’t have easy road access. Unfortunately, security can be an issue, and there historically hasn’t been a lot of funding for fieldwork.

The Late Cretaceous rocks also erode differently. Whereas in the northern Great Plains you tend to get large badlands in the Dinosaur Park Formation or the Hell Creek Formation, in Mexico the landscape tends to weather to form a flatter pavement. The sediments slowly weather down and the dinosaurs are left exposed on the desert, bits of bone scattered among rocks, with cactus, yucca and ocotillo growing everywhere. The bones you do find there have often been there a very long time.

Frontal bone of the tyrannosaur Labocania aguillonae, showing the dark, shiny “desert varnish” that would have formed over thousands of years.

They are typically covered with a thick layer of desert varnish, a dark, shiny crust of minerals and metals that is formed by microbial action. Desert varnish takes an extremely long time to form- a thousand or even ten thousand years— which means many of the dinosaurs you encounter in the field have been slowly eroding out since the end of the last Ice Age. What in turns means is that much of what we find is heavily weathered and incomplete. A few beautiful specimens have emerged but mostly what we find is weathered lag of skeletons that have been laying out in the desert for millennia, dinosaurs that must have been there when the Clovis People were chasing mammoths, and we’re now walking along picking up the few fragments that have managed to survive all those thousands of years. As a result, a lot of these animals— Paraxenisaurus, Labocania aguillonae— tend not to be as pretty as the fossils from the Hell Creek or Dinosaur Park Formation.

Bone fragments from a hadrosaur skeleton weathering out of the Cerro del Pueblo Formation

So given all this, why would one want to work in Coahuila? Well the people are nice, the food is good, and the country is breathtakingly beautiful.

They passed through a highland meadow carpeted with wildflowers, acres of golden groundsel and zinnia and deep purple gentian and wild vines of blue morningglory and a vast plain of varied small blooms reaching onward like a gingham print to farthest serried rimlands blue with haze and the adamantine ranges rising out of nothing like the backs of seabeasts in a devonian dawn. — Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

And then the dinosaurs are extraordinarily diverse, weird, and unique.

Mexican dinosaurs seem to be distinct from the ones we find in the northern USA and Canada. They’re more closely related to the ones in New Mexico and Texas, but still, so far all the species that have turned up are distinct from those in the United States. Mexico had its own dinosaur fauna— and there are a lot of dinosaurs.

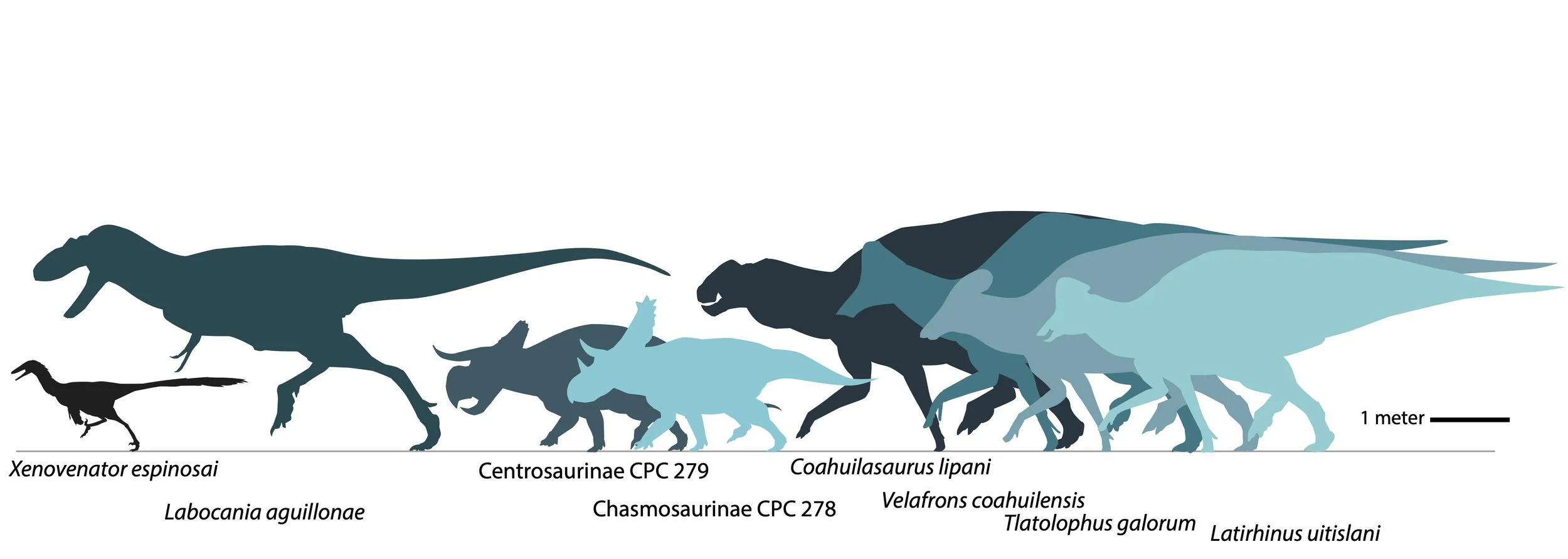

Given the sheer diversity of species that have turned up based on the relatively limited sample from the latest Campanian of the Cerro del Pueblo Formation— there are at least four distinct hadrosaur species— and based on preliminary studies of museum collections, I would guess Coahuila likely had one of the most diverse dinosaur faunas known. In recent years its produced new species like Tlatolophus, Coahuilasaurus, Labocania aguillonae, and there’s still a lot waiting to be described, and even more out there in the desert still to be dug up.

The Cerro Del Pueblo is perhaps not as diverse as the Dinosaur Park Formation. But then, what is? The DPF is so far the most diverse known assemblage.

And the Cerro del Pueblo is maybe not as diverse as the Nemegt— but it’s likely as diverse or more diverse than the Hell Creek Formation. It seems to have twice the diversity of hadrosaurs and ceratopsians as the Hell Creek— so my guess is that this could easily turn out to be perhaps the third or fourth most diverse dinosaur assemblage known in the world. There’s just a lot there waiting to be recognized.

Like the new little Mexican troodontid, Xenovenator espinosai.

A Thick-Headed Troodontid

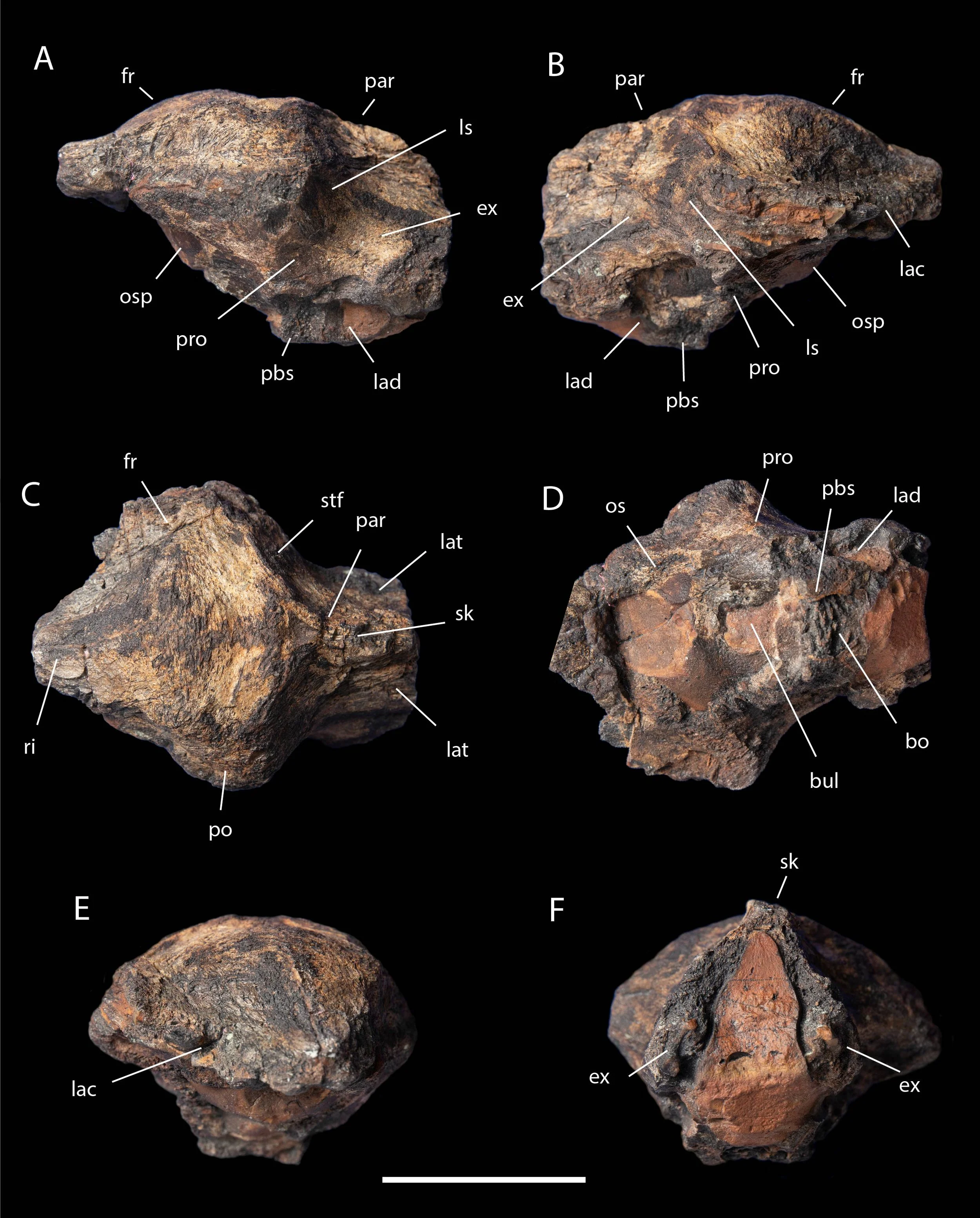

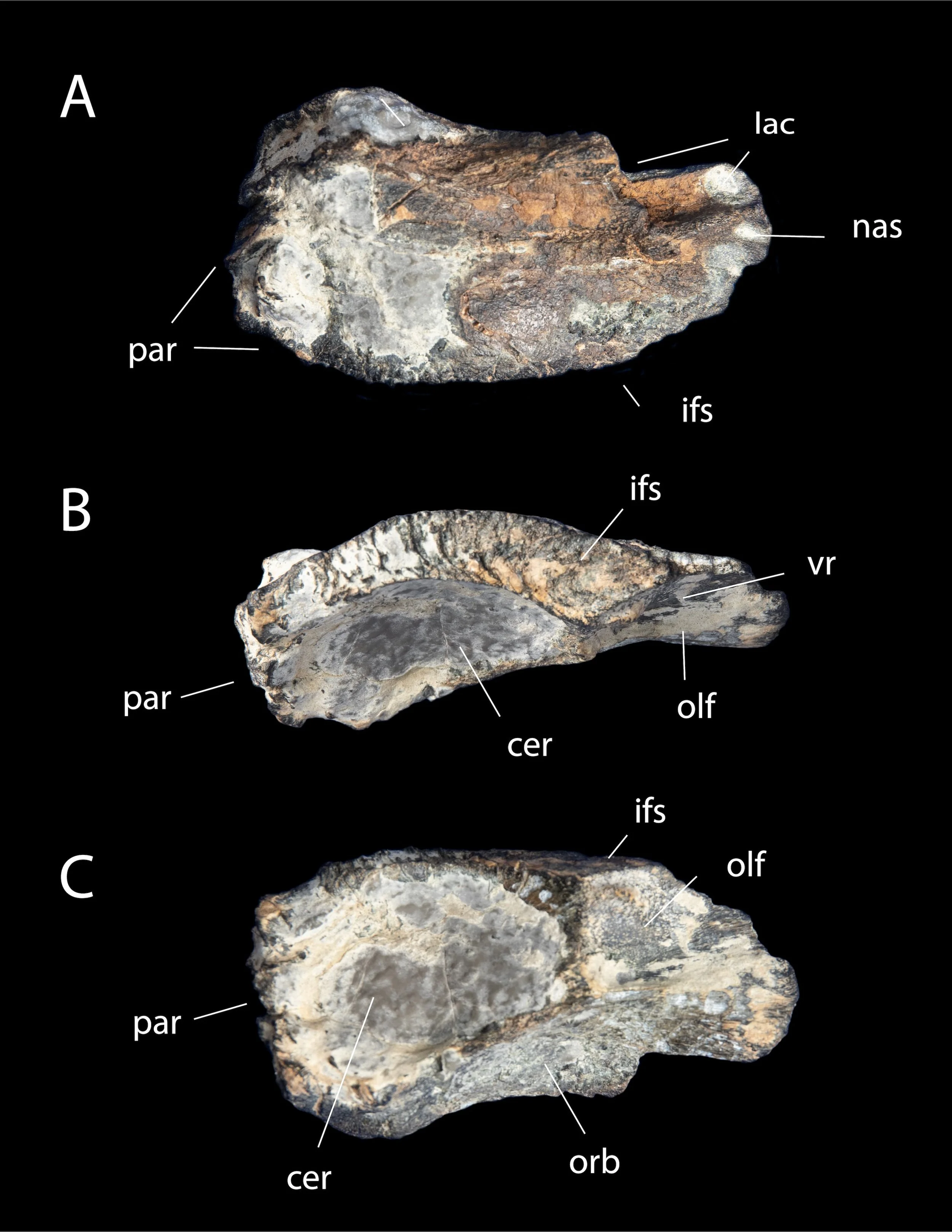

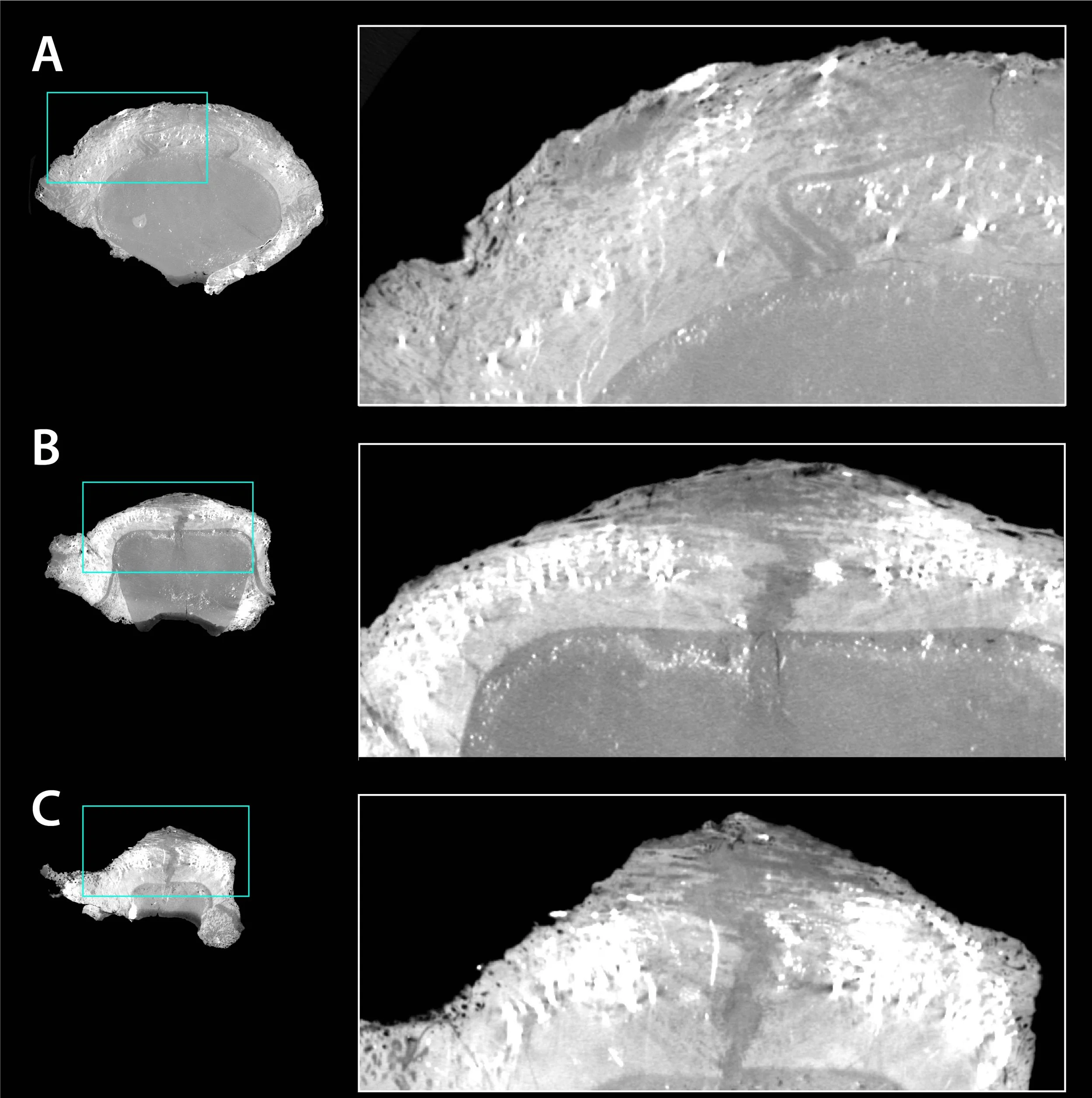

Xenovenator espinosai, holotype braincase.

The partial skull of Xenovenator was originally discovered by the Museo del Desierto in 2007, in a locality near the top of the Cerro del Pueblo Formation that is known as La Parrita. It’s one of the most complete known troodontid skulls ever found in North America. This is not saying a lot to be fair- no complete troodontid skull is known from North America. but this one includes the frontals, parietals, laterosphenoids, exoccipitals, prootic, basisphenoid, etc. And it also shows the typical Coahuila preservation— a beautiful specimen, eroded and covered in desert varnish from sitting in the desert for ten thousand years.

It doesn’t look like much— a slightly irregular lumpy bit of rock. It’s not the kind of trophy specimen you put on display in the center of the museum, but then, the vast majority dinosaurs aren’t. But there is however a lot of anatomical detail here, if you’re willing to sit down and do the detailed anatomical comparisons, and when you do compare it to other troodontids, it looks very, very weird.

The La Parrita troodontid skull was finally given an initial description a couple years ago, and reading that paper I had a strong hunch we were probably dealing with something new. Then couple of years ago, I got a chance to see the specimen, as well as some new isolated troodontid frontals. Two things stood out about these specimens.

The first thing that immediately struck me was the bizarre shape of the frontals— they were strongly convex on top, creating a sort of broad dome, with large shelves over the orbits;.

Second, they were just massively thickened, especially anteriorly— over a centimeter thick, which is a lot for a relatively small dinosaur like this.

The braincase itself was difficult to study— the inside was filled with a layer of dense ironstone— but the exposed lateral edges of the frontals suggested the bones of the braincase were incredibly thick. I had a hunch the specimen would reward CT scanning, so the museum arranged to have the specimen scanned, suspecting we might get some interesting details. We were not disappointed.

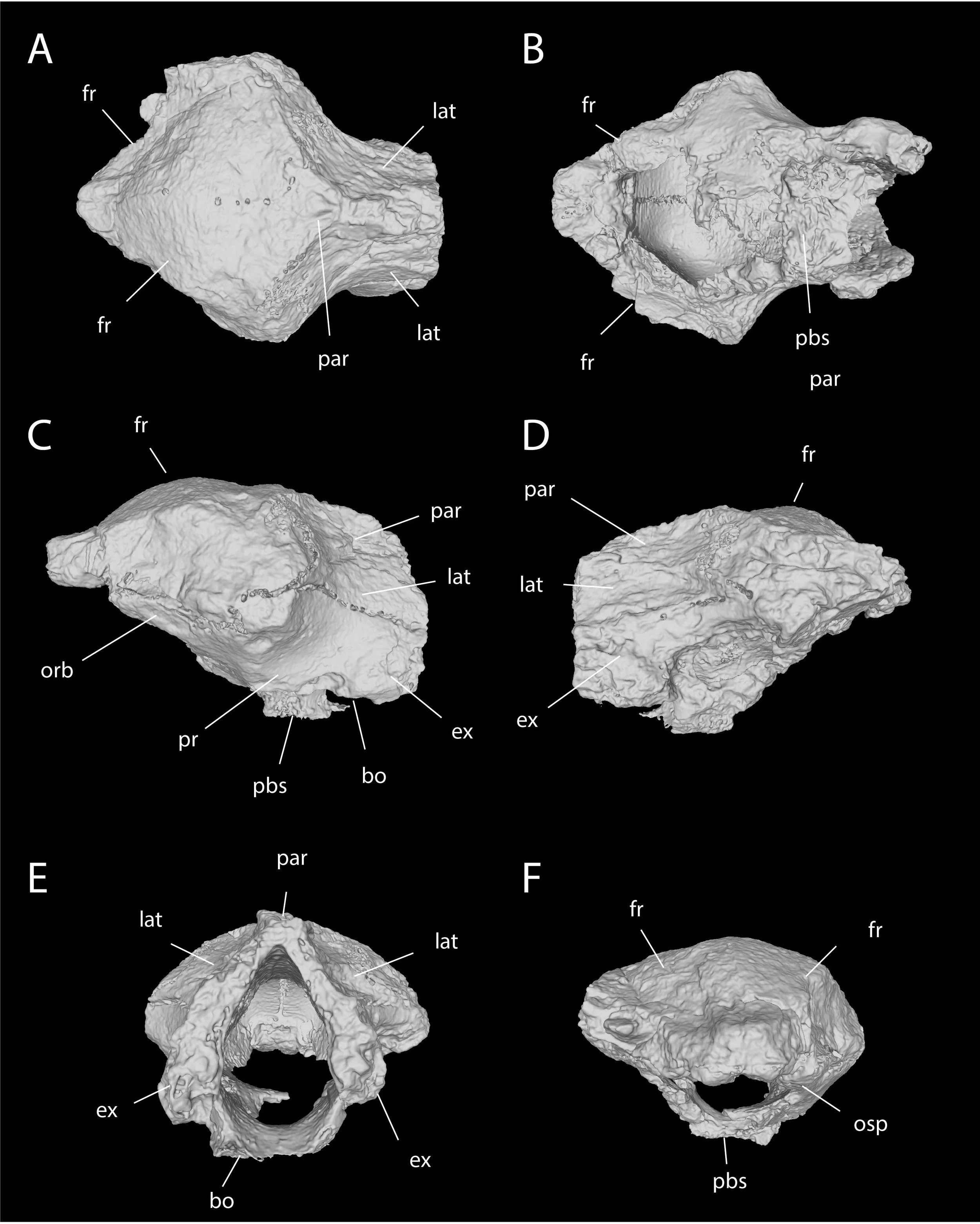

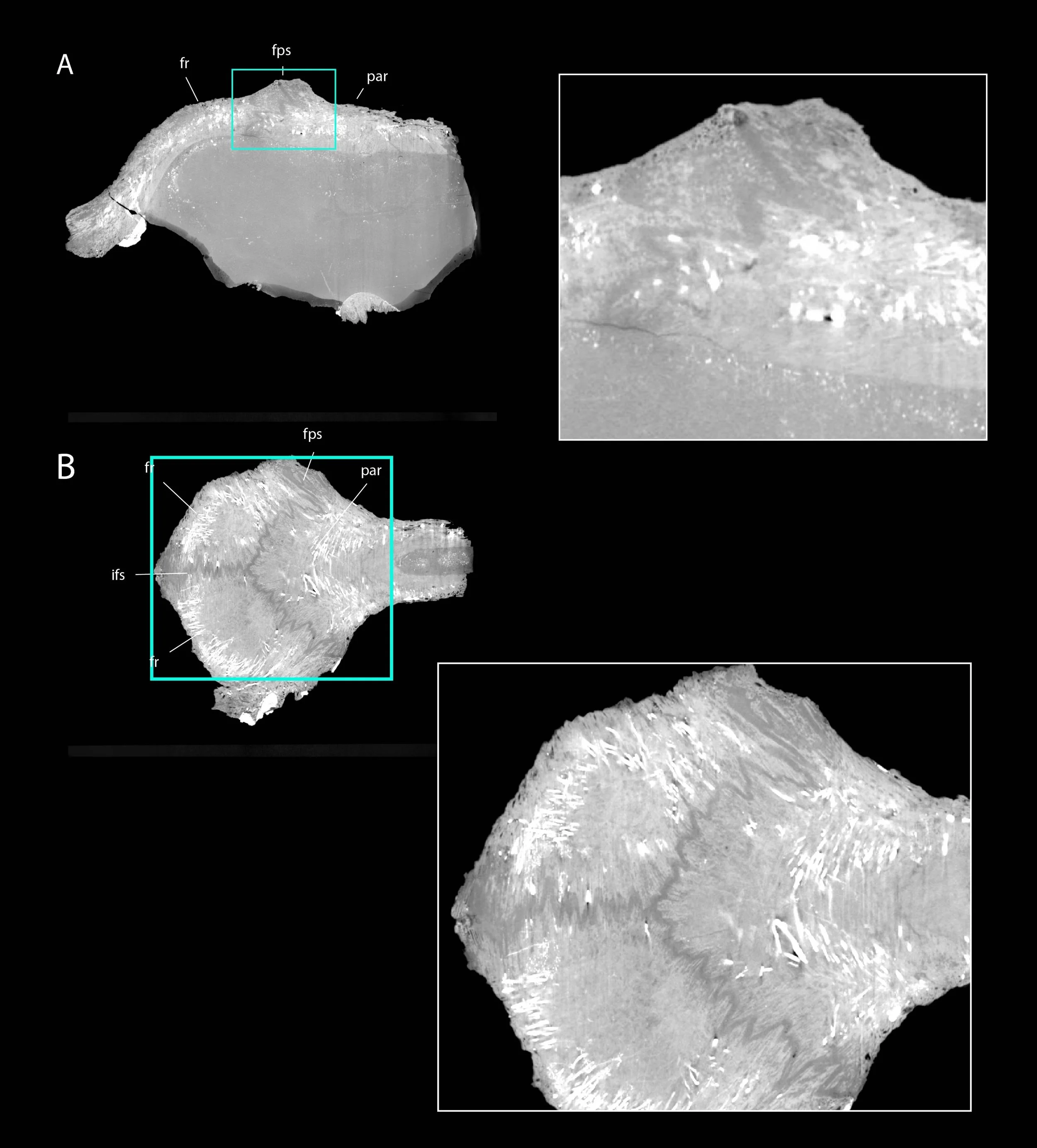

Volume rendering of the Xenovenator holotype skull from CT data.

The entire braincase is massively thickened. The frontals are thickened and vaulted, the parietals are thickened, the lateral walls of the braincase are thickened.

What’s more, the frontals are tightly fused to each other along the dorsal surface of the braincase, and the bones have these bizarre, interlocking, zig-zag sutures.

The texture of the bones is also strange— the dorsal surface of the frontals bears these strings of bone while the internal structure shows pillar-like structures oriented perpendicular to the bone surface.

As weird as it is, the basic anatomy is fundamentally similar to that of other North American troodontids like Troodon and Stenonychosaurus. It’s taken a fairly standard North American troodontid braincase, thickened it, domed the frontals, and created these weird interlocking joints.

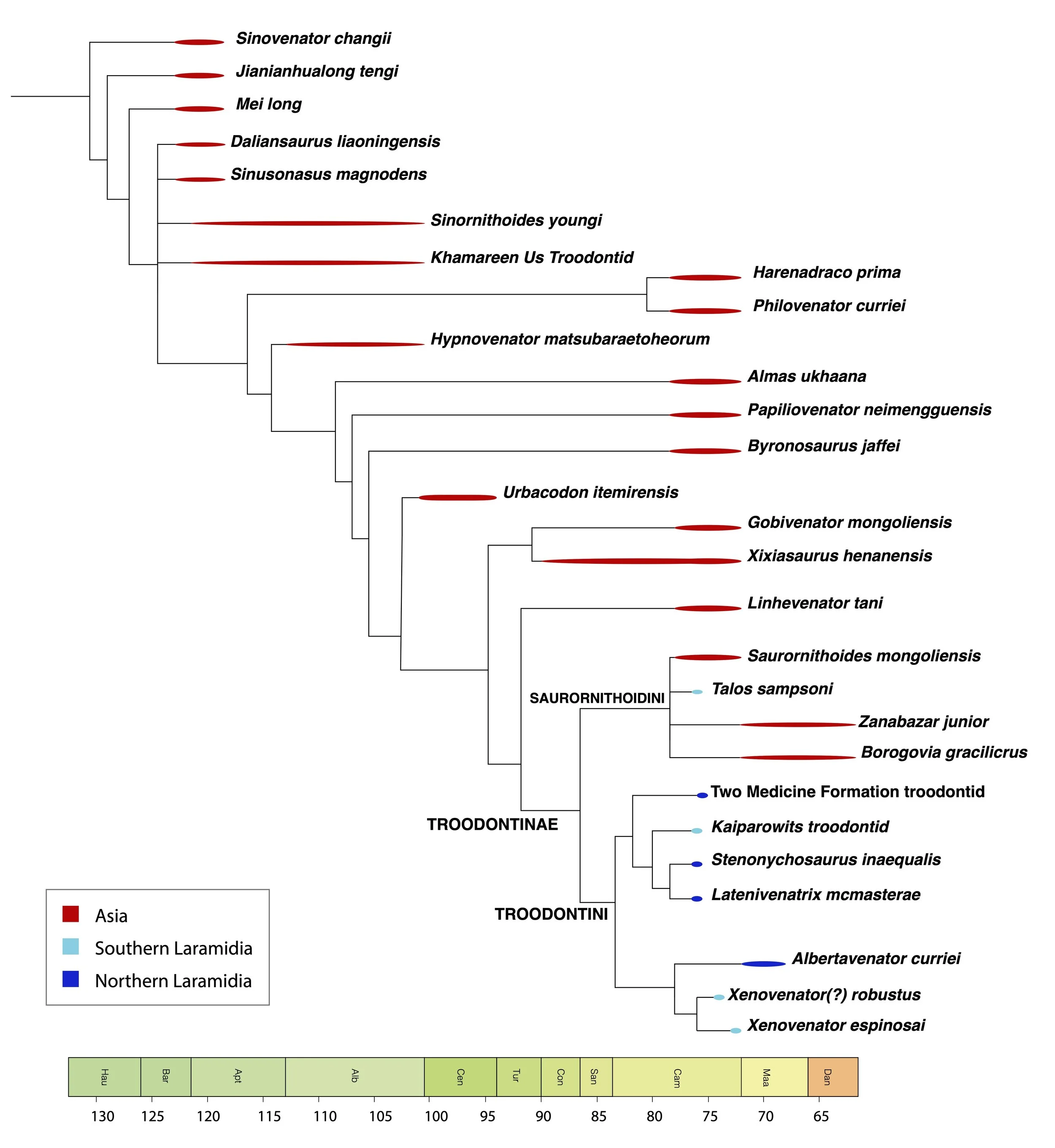

When we do a phylogenetic analysis, we find it nested within a cluster of North American species like Troodon formosus, Stenonychosaurus, Latenivenatrix, and Albertavenator. It may be closer to Albertavenator, given the very broad supraorbital shelves. Curiously, a number of features link it to “Saurornitholestes” robustus- the anteriorly displaced postorbital processes, and thickening along the frontal midline- suggesting that species might be better classified as Xenovenator robustus.

My, What a Thick Skull You Have

So, why did Xenovenator have this bizarre, thick, domed, interlocking skull roof?

Well, the most obvious parallel one can draw is with the thick-headed pachycephalosaurs. The Pachycephalosauridae have a massively thickened skull roof with the frontals, parietals and other bones of the skull being up to several inches in thickness, and the frontals and parietals are vaulted to create a massive dome.

This creates the appearance that pachycephalosaurs have big brains, almost like humans but this is an illusion- the vaulted skull roof in pachycephalosaurs is all solid bone, not hollow braincase. The actual brain is about the size of a walnut and sits under the base of the dome in a small, shallow depression, not inside this dome. The dome sits atop the brain itself.

The function of the pachycephalosaur dome has been debated but the consensus these days is that it functioned as a weapon in head-butting matches, an hypothesis supported by high rates of pathology in the dome, trauma and / or infected injuries incurred by repeatedly ramming their heads together. No other hypothesis seems able to explain the massive construction of the dome or the high rates of pathology seen in it.

Of course it’s a bit tricky trying to guess at the function of a structure in one extinct animal, where function cannot be directly observed, by comparing it to another extinct animal where we also cannot directly observe function, and only infer it.

It’s sort of inference resting on top of inference; which isn’t to say the pachycephalosaur comparison isn’t informative and useful but it has certain limitations.

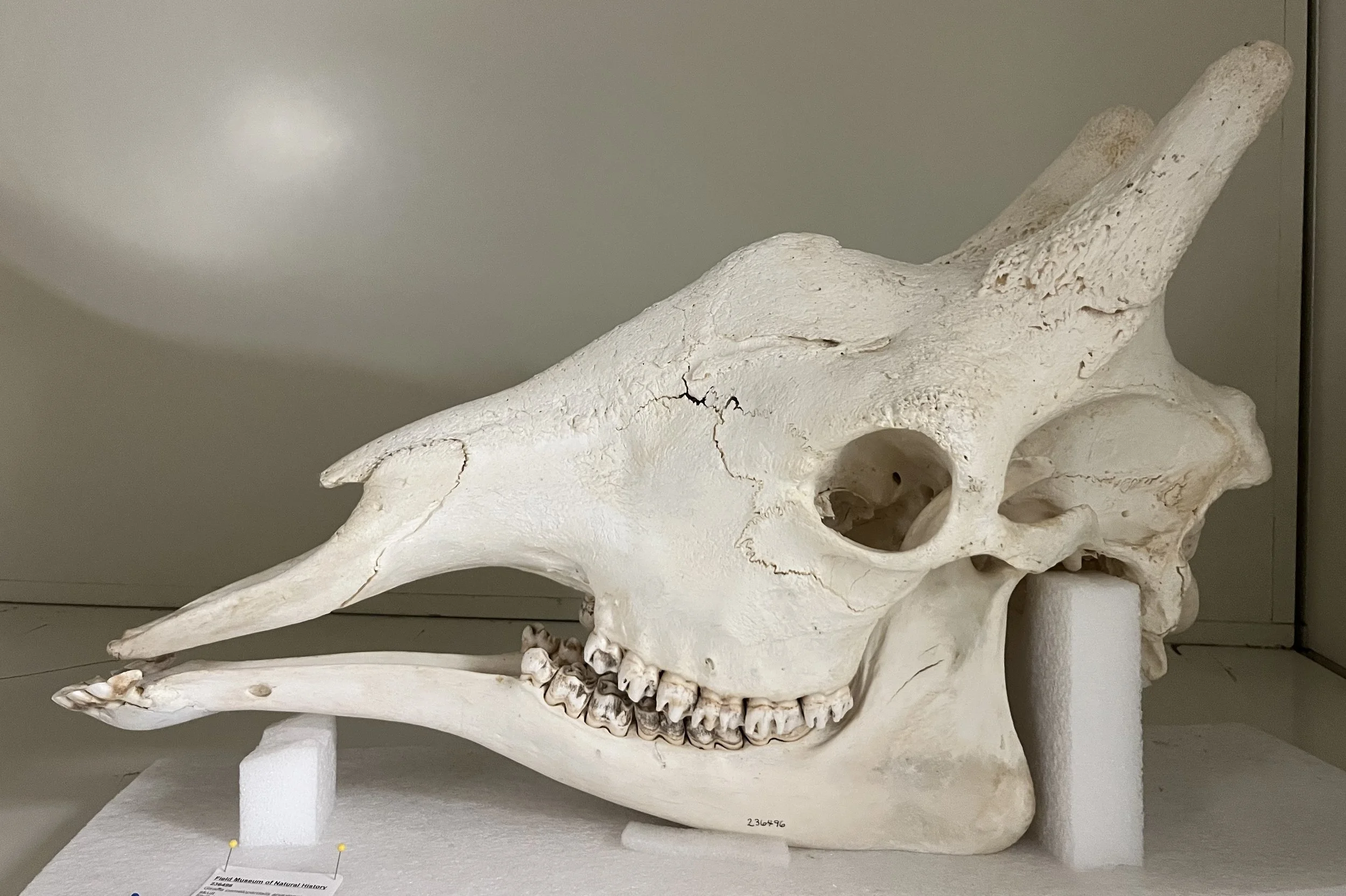

A more reliable way to infer function is to look at modern animals, where we can observe exactly what they do. Again, we see that animals with thickened, vaulted or domed skulls roofs- cape buffalo, giraffe, Sumatran serow, helmeted hornbill- tend to engage in combat, butting their heads together (cape buffalo, serow, helmeted hornbill) or butting each other flanks (giraffe). Many of these animals also have extensive skull fusion and/or complex, interlocking sutures. The fact that Xenovenator resembles not just pachycephalosaurs but multiple taxa that use their heads for weapons is strong evidence that the head is a weapon.

A cape buffalo (Synceras caffer), showing the formation of a cranial dome, used for head-butting, by the inflated bases of the horns.

Giraffe skull, showing the doming of the skull. In some giraffes this dome is topped by a tall boss; giraffes use their domes and horns to strike each other in the flanks rather than directly butt heads.

A display function isn’t impossible but seems unlikely. The dome of Xenovenator just isn’t that tall, so it wouldn’t dramatically increase the profile of the animal,. Yet it’s thick and heavy, so it imposes a high cost in terms of the tissue needed to build it, and the energy required to carry around for the animal’s entire life. This isn’t how you typically build display structures; it’s a big cost in terms of material and energy, while not greatly increasing the conspicuousness of the head, so it seems maladaptive.

A basilisk lizard, showing cranial, dorsal and tail crests used for display in the male.

Display structures tend to be large and conspicuous but relatively lightweight- think of the crest of a guineafowl, or the tail of a peacock, or the cranial and dorsal sail of a basilisk lizard. This maximizes the size of the display structure while minimizing material needed to make it, and reducing the weight of the structure as its being carried around.

Similarly, human signs are made in a similar way: they have a large area to make them conspicuous, but are made of lightweight materials. Humans therefore use lightweight boards, not bowling balls, to make signs.

A sign in Saltillo, Coahuila, advertising amulets, love spells and magic rituals. Note the use of lightweight construction to mazimize display area with minimal cost. Sra. Martha may practice witchcraft, but she still uses materials in an efficient way to advertise her services.

The dome of Xenovenator is very poorly designed as a display structure- maximum cost for minimum display value.

The heavy bone added to the skull instead implies a mechanical function. Likewise, the extensive fusion of the skull roof and interlocking sutures, and the odd arrangement of the trabeculae of the bone all imply adaptation to resist large mechanical loads, not a pure display function- a display structure doesn’t need rigidly interlocking elements, since it isn’t load-bearing (similar arguments apply to pachycephalosaurs, obviously), neither do the trabeculae need to be aligned to resist large forces.

Another curious thing is that the referred frontal lacks many of the more extreme features seen in the holotype braincase. The frontal isn’t as domed, it’s not as thick, the interlocking isn’t as well-developed. Could it be a juvenile? Well, maybe. But it’s about as long as the frontal in the holotype braincase. That suggests another possibility: it was fully-grown but never developed these features, because it was a female. So it’s possible there was sexual dimorphism. We might be able to test this, but would probably need to find a lot more specimens, which is unlikely to happen soon.

It seems then, that Xenovenator had convergently evolved a head-butting function similar to pachycephalosaurs. This tells us a number of curious things.

Mexican Dinosaurs Are Weird

First, Mexican dinosaurs are different from American or Canadian dinosaurs.

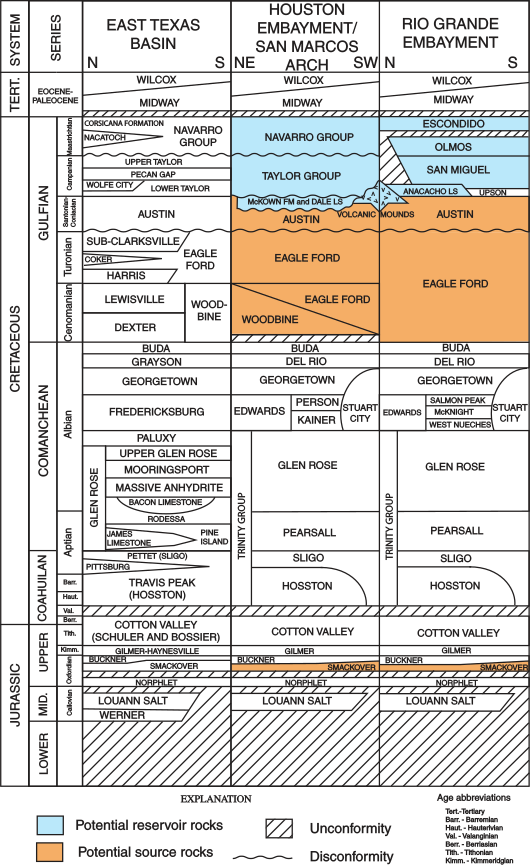

We’re not seeing the same species as we get up north, but a very different fauna. None of the species we find in Mexico are found in similar-aged beds of the Horseshoe Canyon Formation in Alberta. We have entirely different tyrannosaurs— the teratophonein Labocania down south, the albertosaurine Albertosaurus up north.

There are different ceratopsians, with Coahuilasaurus down south and Anchiceratops and Arrhinoceratops up north.

There are different duckbills, with Edmontosaurus and Hypacrosaurus up north, and Tlatolophus and Velafrons down south.

Labocania aguillonae, Tlatolophus and Coahuilaceratops, from the Cerro del Pueblo Formation of Mexico.

There are more similarities between Coahuila, and New Mexico and Utah- Labocania aguillonae appears to be closely related to Bistahieversor from New Mexico, a chasmosaur from Coahuila may be related to Utahceratops from Utah, Coahuilasaurus is related to Gryposaurus monumentensis from Utah. And then that thick-skulled troodontid from New Mexico, “Saurornitholestes” robustus, seems to be closely related to Xenovenator, or a species of Xenovenator.

At some level this isn’t surprising— the Cerro Del Pueblo Formation is 2000 miles south of Montana and Canada, we might expect different species- but even over shorter distances, Canada to Utah or Montana, we see differences, suggesting that species turn over rapidly with distance. You don’t have to go very far in the Late Cretaceous of western North America to find new dinosaurs.

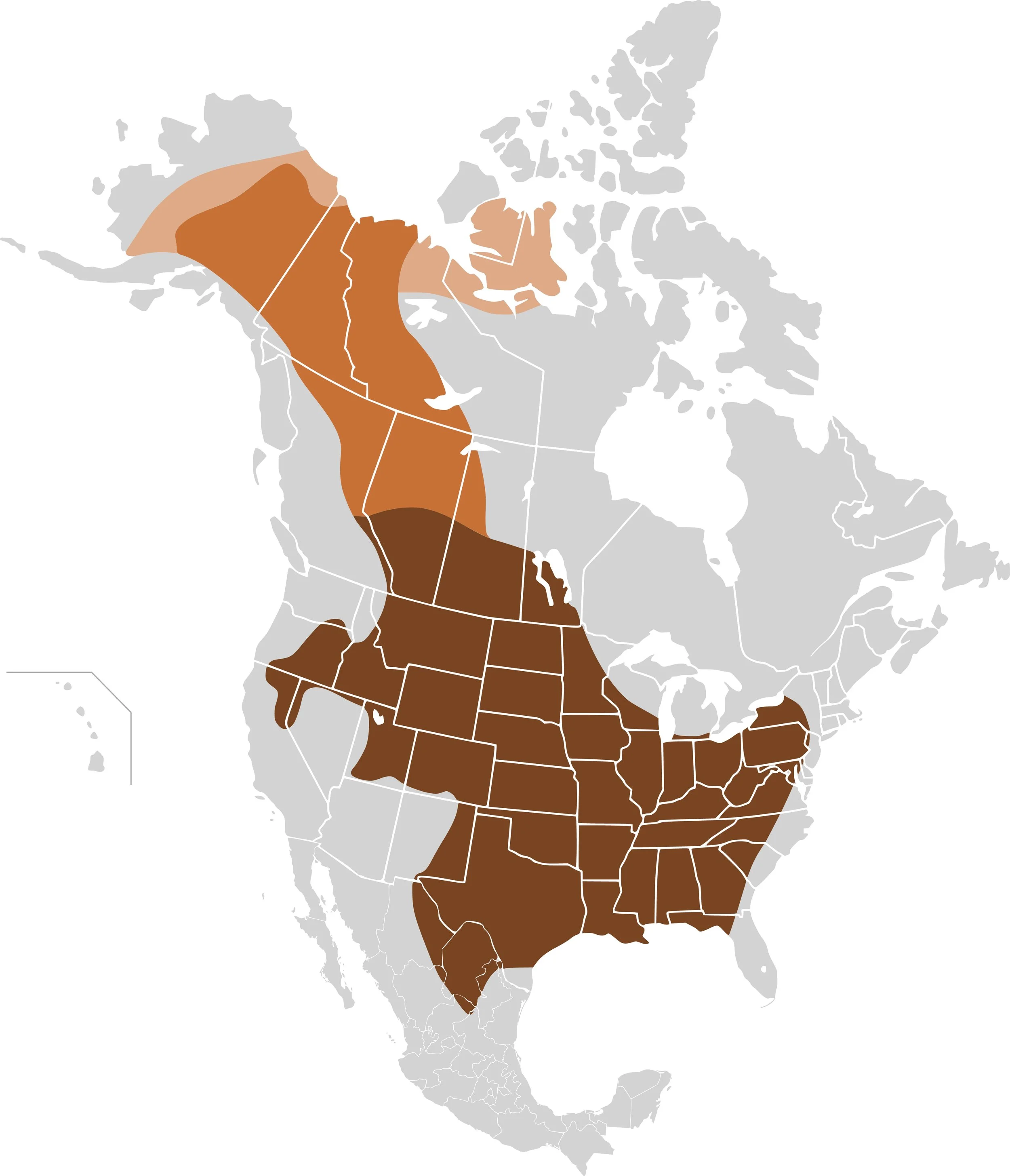

But this isn’t the case in modern North America, where animals like whitetail and blacktail deer, brown bear, black bear and bison range (or historically ranged) from Canada south into Mexico.

Historic range of Bison (Plains Bison in dark brown, wood bison in light brown) in the Holocene, showing a range from Alaska to Mexico.

It’s unclear why dinosaurs and modern mammals have such different ranges. It’s possible the warmer climates of the Cretaceous somehow changed how species were distributed. Alternatively, some aspect of dinosaur biology may have allowed them to specialize more narrowly on habitats, whereas mammals tend to occupy a wider range of habitats.

This obviously has interesting implications for understanding dinosaur diversity. Late Cretaceous dinosaurs seem to have remarkably small ranges- different species in Canada, Utah, New Mexico, Mexico. If so, dinosaurs may have packed a lot of species into Western North America because there were different species in different parts of the continent- and the same is probably true of eastern North America, Asia, South America, Africa, and so on. It may well be that dinosaurs had smaller ranges, for some reason, than modern big mammals like lions, elephants, zebras, mammoths, and white-tailed deer, and soforth— so that they could achieve much higher diversity than similar-sized mammals.

And this has interesting implications for understanding dinosaur diversity in the latest Cretaceous- much of what has been written about dinosaurs in the late Maastrichtian is based on the Hell Creek Formation of the northern Great Plains, but the dinosaurs may have been very different in the south- we know there were species there, like lambeosaurs, kritosaurs, and titanosaurs, we don’t get in the north.

What would be really interesting is to know what the Mexican dinosaurs are doing in the Maastrichtian. The dinosaurs from the Olmos Formation- a giant duckbill known as the “Sabinasaur”, a huge ceratopsid horncore— may be Maastrichtian, and they aren’t closely related to anything we know from the States, even from New Mexico or Texas.

The Olmos Formation may preserve a Maastrichtian dinosaur fauna- and what little is known so far suggests the Maastrichtian dinosaurs of Mexico are very distinct from the those of the United Sates and Canada.

The implication is that Mexican dinosaurs remained distinct into the Maastrichtian, and if we can ever find a good late Maastrichtian fauna in Mexico, we are likely to find a whole host of new species. The fauna is likely to be broadly Laramidian— with lambeosaurs, saurolophines, tyrannosaurids, ceratopsids, troodontids and so on— but with different lineages, specialized in different ways. This is of course just a hunch, but it can be tested- with more fieldwork.

Late Cretaceous Dinosaur Evolution

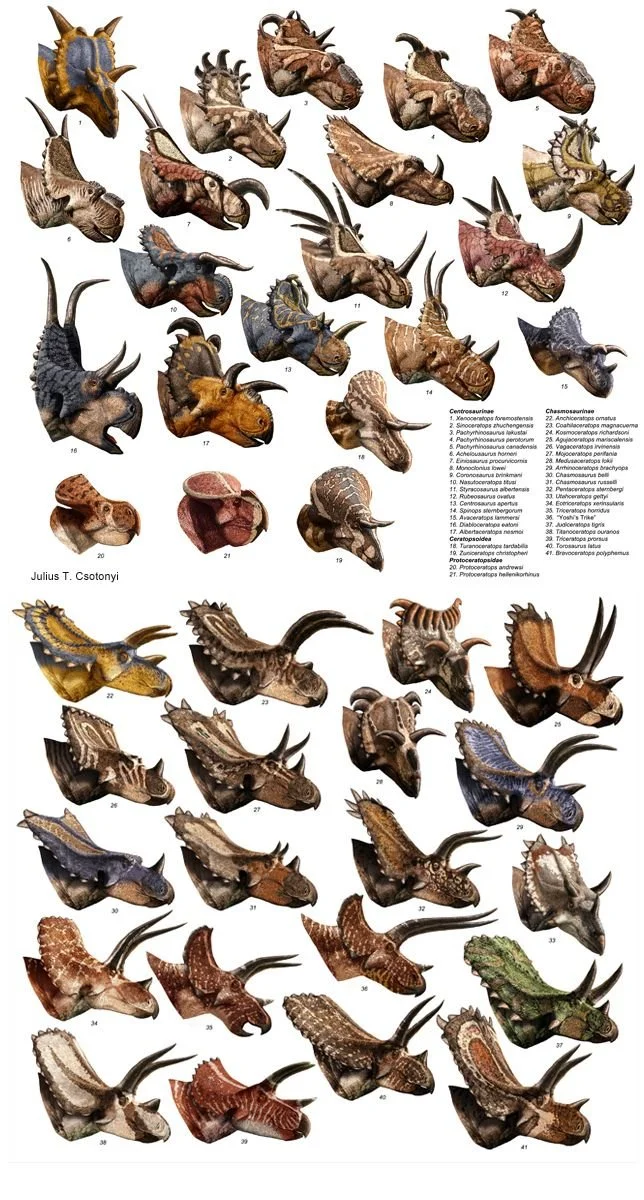

Last, it’s possible that Xenovenator may say something more broadly about dinosaur evolution. The evolution of a thick-headed troodontid fits a broader pattern, I’d argue, where dinosaurs evolved increasingly elaborate ornamentation and weapons over the course of the Mesozoic.

In the Late Cretaceous, we see elaborate crests and horns in ceratopsids. We have horns in abelisaurids like Carnotaurus and Majungasaurus. We have cranial crests in duckbills, both bony casques and crests in lambeosaurines and kritosaurins, and soft-tissue crests in edmontosaurs.

We see fin-backed protoceratopsids and Deinocheirus. We have thick-headed pachycephalosaurids and thick-nosed pachyrhinosaurs with skulls specialized for head-butting.

And now we have a thick-headed troodontid with a skull evolved for head-butting as well. Dinosaurs are becoming more ornate, more ostentatious, more combative, I’d argue.

The Jurassic isn’t without it’s elaborate dinosaurs— there was Stegosaurus with its elaborate plates and spikes, Ceratosaurus with its horns- but the phenomenon of ornament and weapons seems to become much more common, weapons and ornaments become more elaborate and specialized, I’d argue, as we move into the Late Cretaceous. Why might this be?

The common theme of these ornaments and weapons is that they are part of their owner’s social lives. They serve to help court mates, to impress and deter rivals, and if necessary, to fight rivals over territory and mates. They suggest that dinosaur social lives became increasingly complex over the course of the Mesozoic. I appreciate that this may seem speculative. However, we know that dinosaurs increasingly evolved large brains towards the end of the Mesozoic— duckbills had much larger brains than their Jurassic relatives, troodontids like Xenovenator had some of the largest brains known in Cretaceous dinosaurs. And large brains tend to be associated with sociality— many of the largest-brained animals today, animals like wolves, lions, chimpanzees, parrots, ravens, and of course humans— tend to live in large social groups. Big brains are necessary for socialization, for understanding, competing with and cooperating with other members of your species.

Another piece of evidence more directly supporting this argument for increased sociality is the existence of huge bonebeds and mass graves- of ceratopsids like Centrosaurus and Pachyrhinosaurus, of Edmontosaurus, of ornithomimids like Sinornithomimus, the ankylosaur Pinacosaurus, the little oviraptorosaur Avimimus- which suggest these animals are social. I would suggest that these bonebeds and mass graves seem to be more common in the Late Cretaceous (I concede I could be wrong here; it is just my general impression- the proper thing to do would probably be to try to quantify this and see if there really is a trend over time). Its true that there are mass death assemblages known from earlier times- the Allosaurus in Cleveland-Lloyd quarry in Utah, or the Coelophysis at Ghost Ranch- but these seem to represent drought assemblages, animals drawn together by the presence water, rather than necessarily animals that perished together because they lived together.

Seen in isolation, Xenovenator is simply a curiosity— a weird little raptor that evolved a thick head to fight other members of its species.

Seen in the context of Late Cretaceous dinosaurs, however, it seems to fit a broader trend. This trend- dinosaurs becoming increasingly ornate, elaborate, bizarre in their ornaments and weapons- is an indirect manifestation of dinosaur behavior— increasingly complex social lives, larger social groups, competition and courtship— seen in skulls and bones.

When we talk about dinosaur diversity we tend to mostly focus on species, or anatomy— but perhaps more important is the diversity in their behavior. And what these bizarre skulls, horns, weapons and sails hint at is that dinosaur behavior became increasingly diverse, and complicated, towards the end of the Cretaceous.