Pentaceratops aquilonius, the northernmost southern dinosaur

Dinosaur clades seem to have shown strong endemism— but at times shifted their ranges

Big animals tend to have big geographic ranges. Historically, the African elephant ranged throughout almost the entire African continent. Lions inhabited almost all of Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, southern Europe, and India. So it would be logical to expect that dinosaurs— many of which famously grew to huge size— to have large geographic ranges, with similar species found across the Western Interior of North America.

Geographic range of the lion, historic and modern-day.

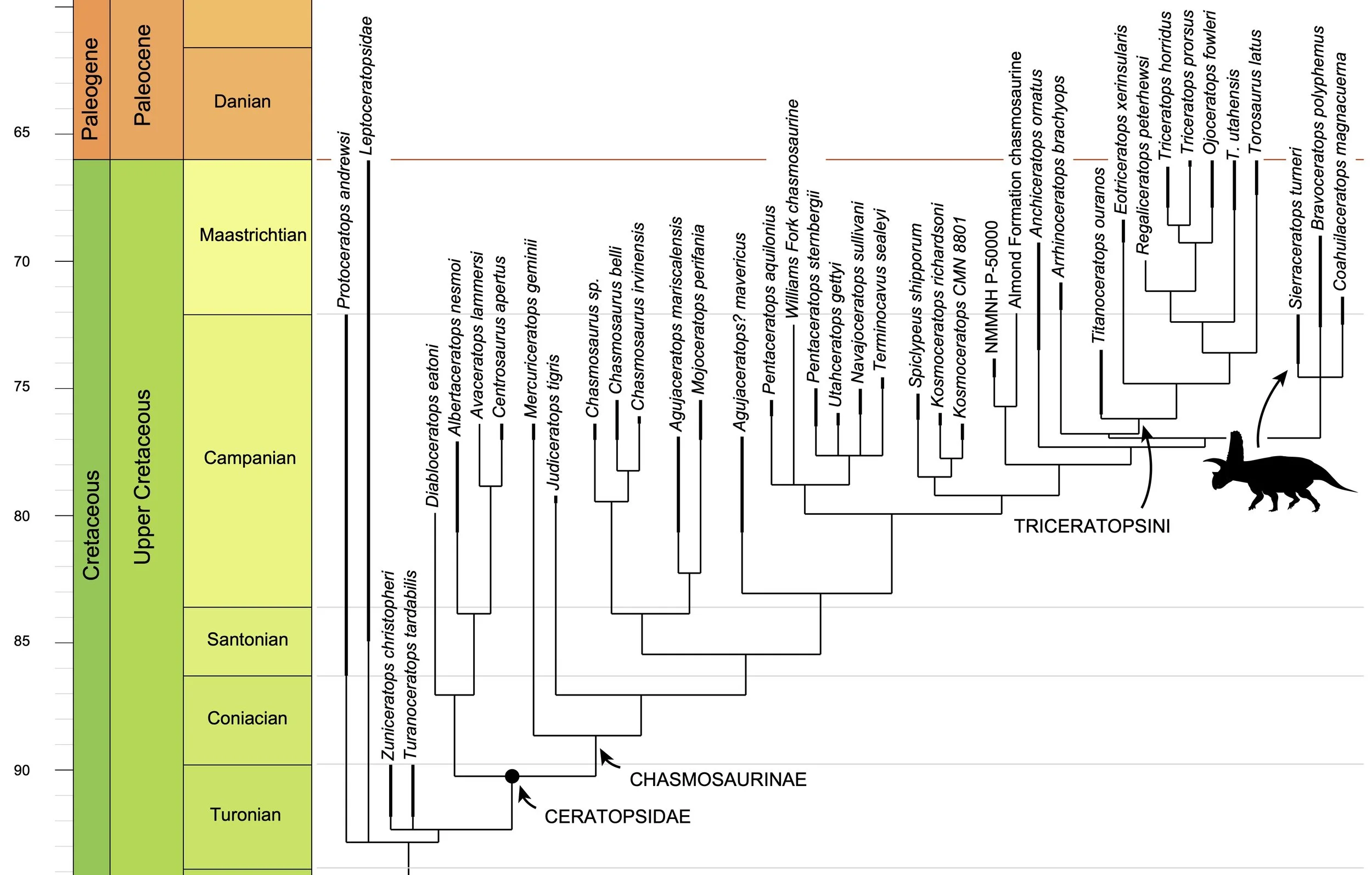

So it was something of a surprise to find that during the Late Cretaceous, very different dinosaur species inhabited different parts of North America— the dinosaurs in Canada weren’t the same as the species in Utah, or the species in New Mexico, or the species in Mexico. We have Albertosaurus in Alberta, Bistahieversor in New Mexico. There‘s Centrosaurus in Canada, Nasutuceratops in Utah. One possible explanation is that these faunas were diachronous- that is, they are different in age, so we weren’t seeing regional differences, but differences in time, caused by speciation and extinction, as a result of sampling different time periods. As we go from Alberta to New Mexico we’re seeing a homogenous fauna, but at different points in time.

But in the past decade or two, we’ve gotten good radiometric dates for these assemblages, and can show that there were different dinosaurs living in different parts of the world, at the same time.

There was endemism- different species in different parts of the Western Interior.

And not just endemic species. In fact we seem to have entire endemic radiations, whole clades that are primarily or exclusively found in either the north or the south. Centrosaurus and its relatives (Styracosaurus, Pachyrhinosaurus, Spinops) are all northern, Nasutoceratops and relatives like Avaceratops never seem to make it north of the Canadian border. The Albertosaurinae extend from Montana into Canada, Bistahieversor and its relatives are primarily found in New Mexico, Utah, and Mexico.

But these groups could and did move around at times. In fact, to have sister groups in the north and south their ancestors must have moved at some point in the past- one population headed south, the other headed north (or vice versa). And curiously, within these clades we also seem to have strays, mostly lineages that spread from their southern epicenter into the north.

One seems to be the Pentaceratops group.

Pentaceratops is found in the Fruitland-Kirtland formation of New Mexico, along with its relatives Navajoceratops and Terminocavis, Utahceratops in New Mexico, and possibly a chasmosaur from the Cerro del Pueblo Formation of New Mexico. But curiously a few of these animals seem to stray up north. One is a Pentaceratops-like animal from the Williams Fork Formation of Colorado.

And one is a scrappy chasmosaur known from the uppermost Dinosaur Park Formation of southeastern Alberta, near the town of Manyberries. It known from a couple of frill pieces described by Langston in 1959, which I redescribed as Pentaceratops aquilonius in 2014.

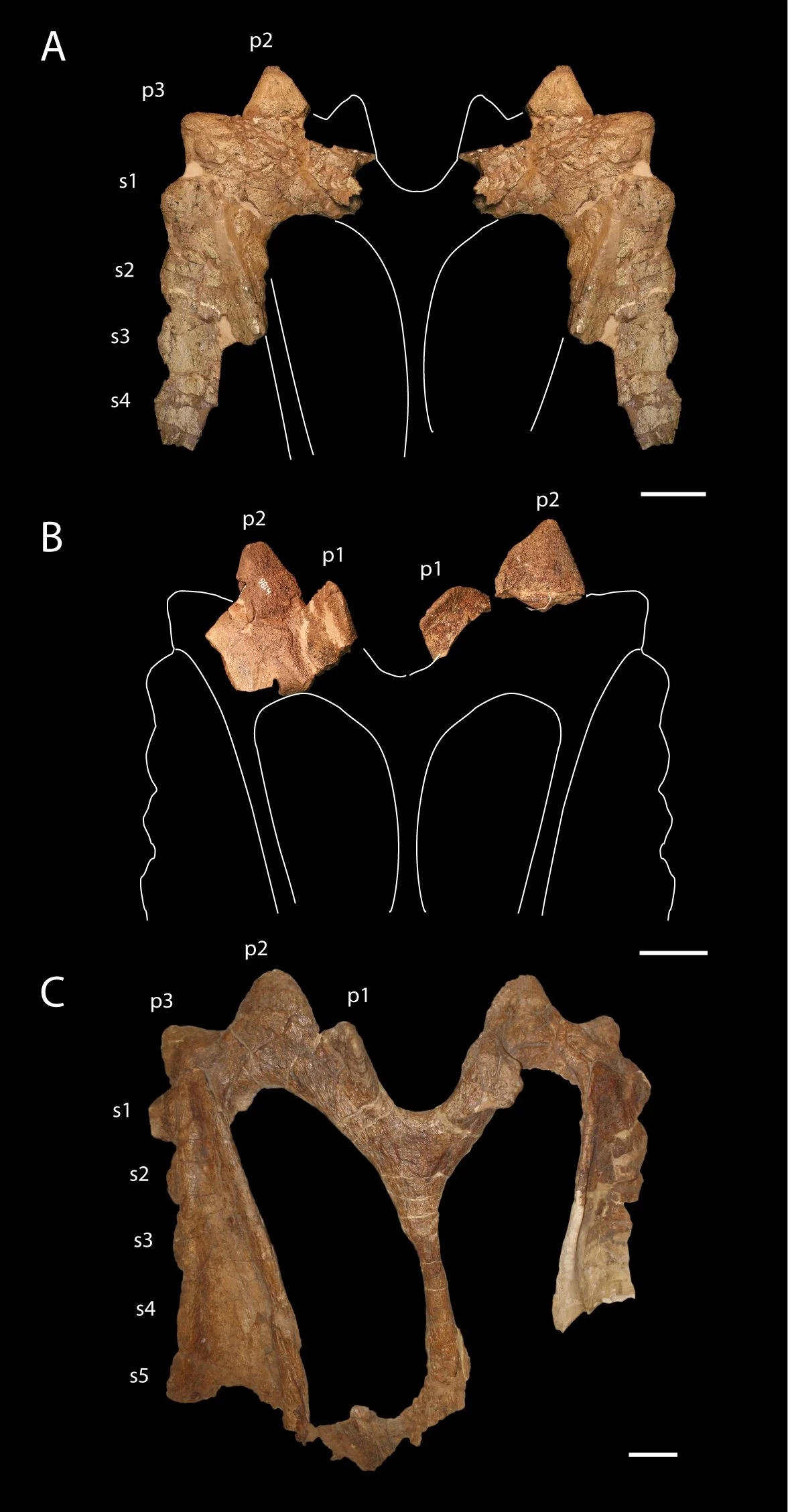

A, B, Pentaceratops aquilonius from the Lethbridge Coal Zone of Dinosaur Park; C, ?Pentaceratops sternbergii from the Fruitland Formation of New Mexico.

These are not pretty specimens- one consists of parts of the parietal, the other the lateral edge of the parietal and the end of the squamosal. But ceratopsian parietals are highly diagnostic (Chasmosaurus belli was named on a partial parietal, for example), so a few years ago I named it as Pentaceratops aquilonius.

Now, I concede a better understanding of the Pentaceratops complex could well result in these things being placed into a larger number of genera, so maybe Pentaceratops(?) aquilonius is more appropriate.

Langston originally referred this animal to Anchiceratops; I disagree with that, but agreed it didn’t fit into Chasmosaurus, Mojoceratops or any of the known chasmosaurs. It does seem to fit well with Pentaceratops.

The Reinterpretation

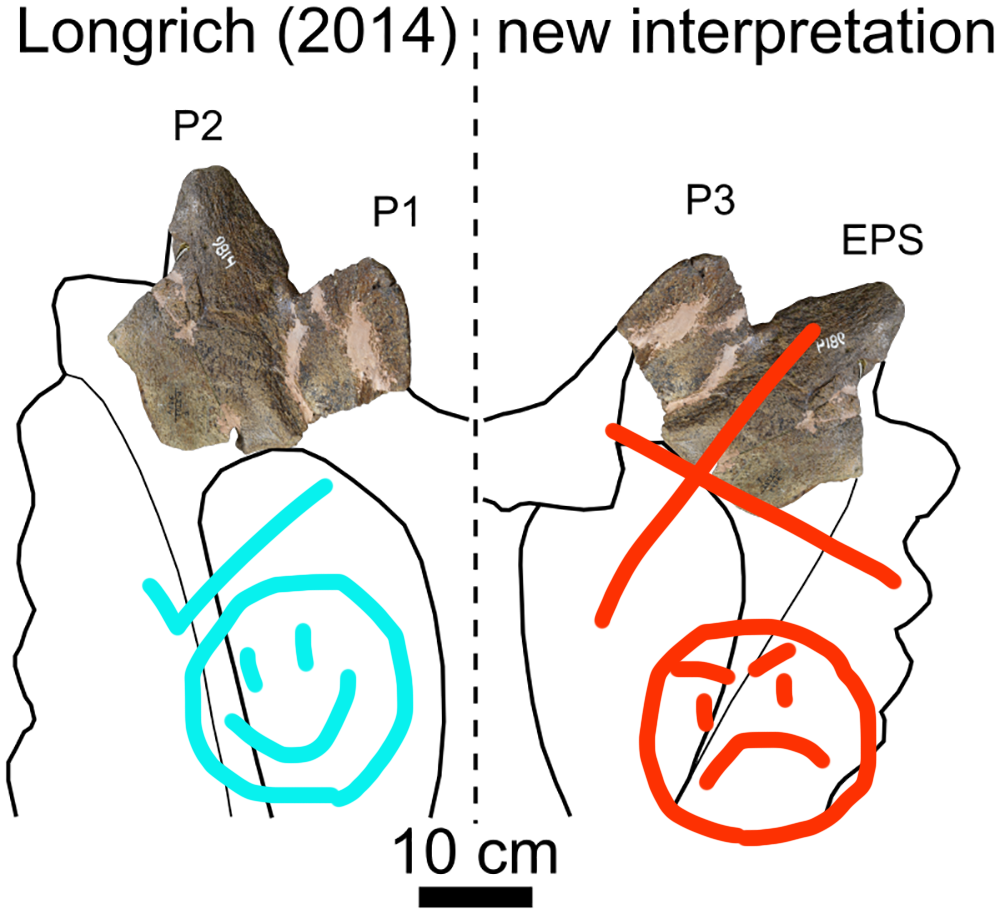

Recently, an attempt was made to reinterpret the partial parietal as more similar to Spiclypeus.

This. Is. Wrong.

The problem is that this interpretation relies on the edge of the parietal articulating with the squamosal. But for the bones to articulate there must be an articulation— a sutural contact, which in ceratopsids is either a butt joint (a flat contact where two elements abut) or a scarf joint, where one overlaps the other (as in Pentaceratops, where the squamosal overlaps onto the parietal).

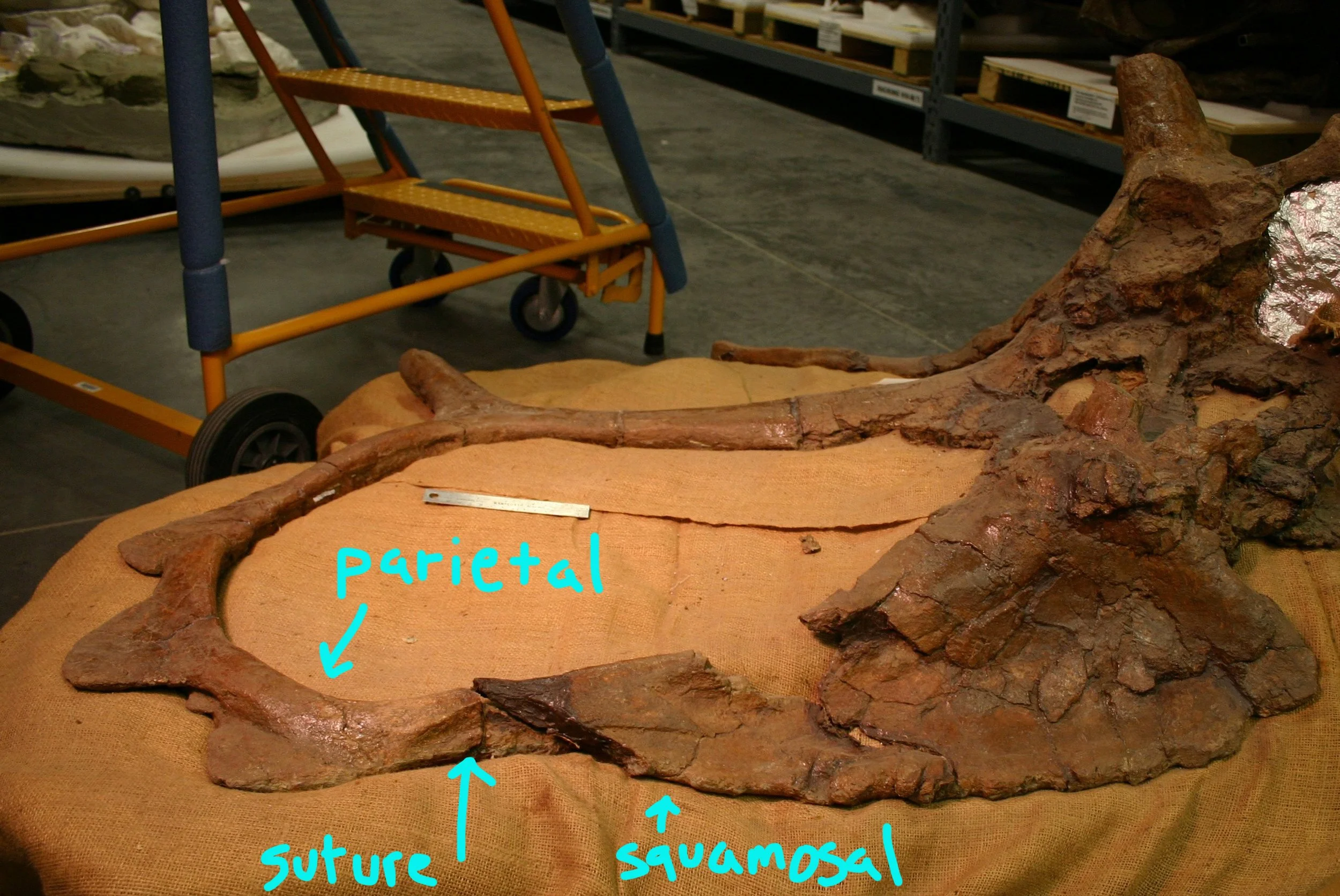

Holotype of Mojoceratops, showing where the distal tip of the squamosal is broken away to expose a broad, concave articular facet/suture on the parietal.

This articulation is difficult to see in most ceratopsians since it’s hidden by the squamosal, so you rarely get to see how elaborate it can be, but in the holotype of Mojoceratops (above) you can see how large and well-developed it is, there’s a huge facet where the two bones of the frill met and the squamosal overlaps onto the parietal.

If the P. aquilonius parietal did articulate with the squamosal, then there should be a squamosal suture at the point of contact. However the squamosal surface here is rounded and has the typical texture of the edge of a frill; this is the frill’s posterior edge.

It is NOT the contact with the squamosal.

Pentaceratops aquilonius paratupe, showing the rounded edge of the parietal, as is typical of the caudal margin of the parietal- not the squamosal.

You can’t just magically force bones into any configuration you want, you have to follow the sutures and carefully study the anatomy to get them in the right place, which was not done with the "reinterpretation”. So the original interpretation of the frill by Langston and myself stands. And following that, the overall shape of the parietal-squamosal frill and especially the twisted-upturned epioccipital put this animal somewhere in the Pentaceratops cluster.

Anyway, I have tried to not get too dragged into these taxonomic/anatomical debates. I would prefer to just publish papers and let the work speak for itself. The problem is that the “let the work speak for itself” strategy doesn’t always work, because people often can’t be bothered to read the papers closely or go back and study the original anatomy. So this leads to errors and misconceptions being perpetuated if they’re not contested. I’d like to think that in science the correct interpretation wins out, but the reality is that when errors like this is put into the literature they tend to persist, and we end up with a poorer understanding of the fossil record as a result.

The other reason that the original interpretation is probably the right one is that the other specimen, the parietal/squamosal frill, shows the typical Pentaceratops arrangement. If the parietal fragment is a Spiclypeus-like animal, then this other frill piece must be something else… yet ANOTHER new chasmosaur, in the exact same stratigraphic horizon?

That’s not exactly impossible, but it’s significantly less likely than there just being a single species.

Dalman, Lucas, Jasinksi and Longrich, 2022.

In short, the original interpretation holds up. The Manyberries chasmosaur is a pentaceratops-like animal. It seems to have been relatively primitive, if (as reconstructed it has a weak parietal notch, but more complete fossils could show otherwise.

“If the parietal does not fit, you must aquit.”

In short, for the parietal and squamosal to fit closely together there must be an articulation— a very tight fit, like a hand in a glove.

If the glove does not fit you must aquit

So what does this all mean?

I do think there’s something to the idea of southern endemism. The epicenter of diversity of many clades— the Pentaceratops clade, the gryposaurs, parasaurolophins, teratophonein tyrannosaurs- is clearly southern, that’s where the bulk of the diversity is found. But in each case, at least one member gets up into Montana or even into southern Canada.

My hunch is that the south is a major center of dinosaur radiation, and tends to export dinosaur diversity north— in general, lower latitudes tend to have higher speciation rates and so pick up more diversity, and they tend to export diversity to low latitudes more often than high latitudes.

Towards the end of the Campanian, however, the northern members of these southern clades- pentaceratpsins, gryposaurs, parasaurolophins, teratophoneins all disappear. Gryposaurs hang on into the late Maaastrichtian in New Mexico and Texas, the other clades are not known from the U.S. or Canada after the Campanian. Why? Who knows. It was getting cooler, so maybe the southern clades were less cold tolerant.

A couple thoughts.

First, the details matter.

Trying to tease dinosaur biogeography apart requires an accurate understanding of the distribution of clades and relationships and memberships of these clades, which in turn requires an accurate understanding of the anatomy of the specimens. Even the interpretation of a single anatomical character can force a complete reinterpretation of a specimen. The reconstruction of where the squamosal suture goes in the Manyberries chasmosaur produces two radically different and incompatible interpretations of the anatomy and therefore the affinities of the animal, which in turn creates completely different biogeographic patterns. In paleontology, where we have very little data to work with, even a few incorrect observations— or even one incorrect observation— can lead to incorrect conclusions.

Second, in science, newer is not always better.

It is not always the case that new interpretations are more accurate than old ones. There is a very strong incentive in science to say something new— science rewards novelty— which often means we end up reinterpreting things that don’t need reinterpretation, trying to force new, incorrect frameworks onto old, solved problems. In the case of a scientific controversy it is often worth re-examining the old work and in general old works often reward careful study. This is true not only in minor disputes over ceratopsian taxonomy, but in science more generally.

References

Dalman, S.G., Lucas, S.G., Jasinski, S.E., Longrich, N.R., 2022. Sierraceratops turneri, a new chasmosaurine ceratopsid from the Hall Lake Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of south-central New Mexico. Cretaceous Research 130, 105034.

Longrich, N.R., 2014. The horned dinosaurs Pentaceratops and Kosmoceratops from the upper Campanian of Alberta and implications for dinosaur biogeography. Cretaceous Research 51, 292-308.

Mallon, J.C., Ott, C.J., Larson, P.L., Iuliano, E.M., Evans, D.C., 2016. Spiclypeus shipporum gen. et sp. nov., a boldly audacious new chasmosaurine ceratopsid (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Judith River Formation (Upper Cretaceous: Campanian) of Montana, USA. PloS one 11, e0154218.